Originally posted on the Aspiration blog

This blog entry written with substantial input and support from Meredith L. Patterson.

Aspiration has taken on Weaponized Social as an extension of our commitment to solidarity with our community and to equality in our interactions with and through technology.

Better Tools for a Better World

Our work to support more people in their existing efforts by making use of technology has a peripheral effect of bringing historically marginalized populations into online space. And as the ever-larger online community welcomes new people, we have not only an opportunity, but also an obligation, to do so with more intent and understanding than society has tended towards in the past. When we speak of online intimidation or harassment, regardless of the perpetrator or recipient, culturally we struggle with issues of accountability, enforcement, and identity.

It’s a Disaster

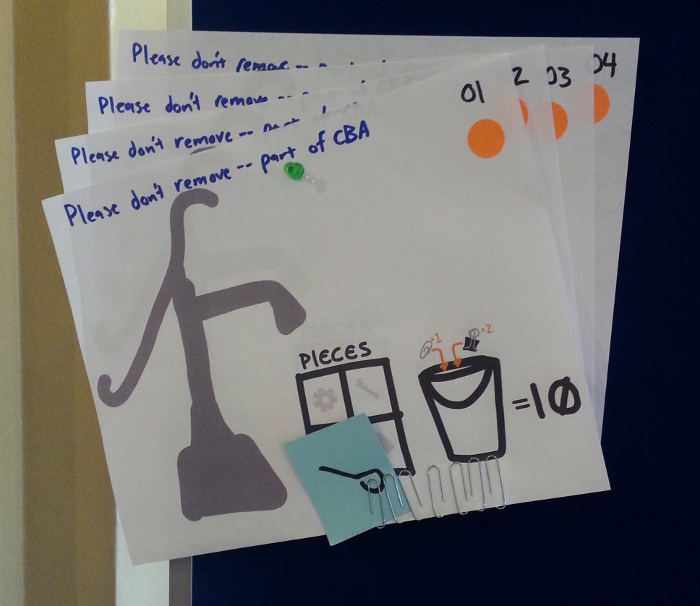

We’ve had a few events (NYC, Nairobi, and San Francisco). From these, and ongoing conversations on the mailing list, the wiki has been expanded and cleaned up. It now includes clearer indicators of how to make use of it, as well as a restructuring into the same framework as the disaster cycle. The disaster cycle falls into preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation. More details on these, along with the added aspect of being an extreme event, can be found on the wiki, with projects and resources listed below each aspect of the cycle. Event notes and project specs continue to also be hosted on the wiki. What are not found on the wiki are academic resources (which can be found in this literature review compiled by friends), nor organizations and initiatives (which Tactical Tech recently curated here).

This approach was taken because many conversations in this space are derailed when discussion of intentions and tactics are conflated. For instance, #hoodsoff revealed the identity of those both in positions of political power AND who were members of the KKK using the same tactics which those same activists might find untenable in regards to doxxing of visible feminine gamers. Or that the tactics used against Brianna Wu and Chris von Csefalvay match at a pattern level that goes beyond that specific instance of escalation. This is where Weaponized Social seeks to explore and intervene, because human rights apply to everyone, including ourselves and whoever we might perceive to be our enemies. “Lead by obeying,” as the Zapatistas say.

Who Watches those Watching the Watchmen?

On the same note of rules applying to everyone equally, including the rulers, and of making the conversation clearer, the Weaponized Social crew has also been ruminating a fair amount recently on how accountability and enforcement factors into all this. When people treat each other in unethical ways, our current social systems indicate bringing the law (and associated enforcement) to bear on those breaking the rules. But we are currently facing a long-overdue distrust in enforcement, especially in police. So just as we’re running into the network effects of negative human interaction, we also have no successful foundation to build upon to mitigate through enforcement. The conversation is therefore further confused by asking who should be holding whom accountable, how do we know that’s being done fairly, and how does enforcement happen? Some are turning to community, some to law, some to software platforms, some to police, etc. Each of these may become a viable option. It’s more likely to be a combination therein, and it’s important to think about the historical patterns of enforcement as well as the repercussions of unchecked social errors.

What’s Missing?

The glaring hole which was surfaced by restructuring projects and pieces into this framework is a complete lack of recovery (it’s also totally possible that I’m just not aware of it. If you know of any, please send them our way!). Preparedness and response are necessary and worthwhile aspects to cover, but we offer no long term support or recompense to those who have been affected by the weaponization of social so as to make them whole again. Even legal and policy interventions seem to linger in only half of the cycle, when arguably institutions are responsible for longer term stability (leaving the network to adaptation). This is heartbreakingly familiar, as it’s the same in response to offline disasters.

Additionally, as the conversation expands and deepens, more individuals and organizations are beginning to see their responsibility in encouraging healthy interactions. A few requests have now come in for guidelines in making tools and platforms which take into account these issues. We’ve started to describe the various vectors of online communication which might be fiddled with, and we welcome your feedback!

What I’m excited about is how much of the Weaponized Social crew (most notably, Meredith and TQ) has focused on the mitigation aspect of the disaster cycle. How can we change the very way we do things, to become more pro-social for everyone? We welcome your perusal and contributions to any of the projects on the WeapSoc wiki, but these are the ones I’m most excited about.

What’s Next?

What’s up next is a discussion with Meredith et al to historically, theoretically, epicyclically, technically explore the weaponization of social interaction, such that we can arrive at better interventions. To start, we might discuss the history of liberal social justice and identity politics social justice, cognitive biases, and network effects. You can tune in December 18th at 11a PT / 2p ET by registering here.

We’re also starting to explore a code sprint on some of these tools. If you’d like to get involved, please let us know!