Originally posted on the Truss blog

When building systems with threats in mind, it’s not enough to just plan, not enough to just raise the cost to a bad thing happening — we still have to have an idea of what we’ll do when the bad thing happens despite our best efforts.

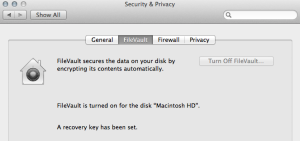

Truss modernizes government and scales industry through digital infrastructure. Information which is sensitive to individuals and to the welfare of the organization flows through the pipes we set up. Whether hospital records, the move locations of a military family, or financial data, Truss takes the best care possible in setting up infrastructure which mitigates the likelihood of a breach. We also have a plan for such a breach, in case it happens anyway.

At RightsCon, I moderated the panel The Rules of Cyberwarfare: Connecting a Tradition of Just War, Attribution, and Modern Cyberoffensives with Tarah Wheeler, Tom Cross, and Ari Schwartz. The question was this: if “cyber”* is a fifth arena of war (the existing domains being land, air, water, and space) what is a just response to a cyberattack which follows the international expectation of deescalating?

The panel and audience knew that the responses which are happening now — the assumption of “hack back” against other state adversaries, the use of CFAA against people who might otherwise entertain the thought of being a patriotic hacker — we don’t agree with. The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) is what makes breaking those terms of service that are too long and dense to read fully a federal crime. That’s right, logging into your partner’s bank account after their death in order to pay the house’s electrical bill is a federal crime, and it’s the same law that’s used in most of the “hacker” cases you read about in the news. It’s also the number one reason the infosec professionals I know and love refuse to work with the government. The ACDC bill which allows “hacking back” is an exception to CFAA which means you can attack a computer that’s attacking you. Except of course it’s not that clear-cut.

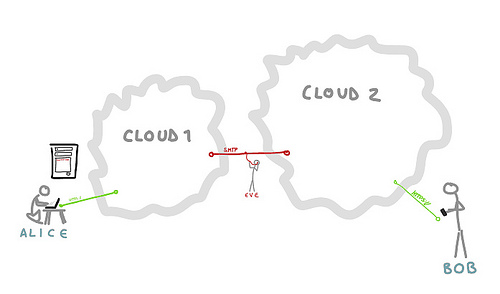

Which brings in the questions that many folk in the audience had. What about attribution (the ability to know who is taking the action)? This is hard in digital space because it’s easy to attack something from behind someone else’s IP address. What about asymmetry (an imbalance between those in conflict with one another)? Is it ok if one country attacks the other in cyberspace when the other country is just beginning to get online? These are hard problems, but we can’t wait until they are solved to have conversations about responses. If you’re having a hard time moving on without those hard problems being “solved enough” first, you’re not alone – the audience also had a deeply difficult time with it.

But what would be acceptable? If there was a breach of military moving data, do you think it would be responded to differently than the malicious changing medical records? Do you think who the adversary is would matter? Does the immediate or the potential future impact on those involved matter more? Where is the line between war and espionage? We ended the panel with the a comparison to disaster response, so attendees would have a framing to continue the discussion.

Disaster response also focuses on preparedness (stockpiling water for the next Bay Area earthquake), response (digging our neighbors out of the rubble), and mitigation (enforcing building codes which make collapse in an earthquake less likely). We are terrible at recovery. When it’s time to rebuild, the money, attention, and volunteers have dried up. Huge swathes of Far Rockaway (2012) and New Orleans (2005) are still a wreck from hurricanes.

The same is true for online attacks — whether doxxing (the nonconsensual revealing of personal information) or DDoSing (a distributed denial of service attack is when many computers all pester your computer for a response, not allowing it to say anything). We spend so much attention on battening down the password hatches and doing incident response that most don’t think about what being whole again after an attack that might happen anyway looks like. And so much of infosec and government work is about trying to prevent the Bad Thing from ever happening. Plan A is to make a perfect system. But we must own up to Plan A rarely being the plan that works out. Don’t your contracts also have release clauses in them? Planning for worst case isn’t inviting calamity, it’s being pragmatic.

One of our engineers recently said, “I would rather throw away some work than have to be under a too-tight deadline later.” This was said as Plan A seemed less and less likely due to bureaucracy and too many moving parts. But Plans B and C were being procrastinated on by our government protective cover. Why? I see the cost of exploring options in government as high, with extremely limited resources to work with. This means all sorts of fragility and resources wasted putting out fires when Plan A didn’t work exactly as planned. A balance of ownership, accountability, and flexibility would have helped alleviate this difficult situation. Additionally, setting aside resources for recovering from inevitable failure helps the entire system be more robust.

While Truss doesn’t specialize in the actual recovery (there are firms and insurance providers who do focus on response and recovery plans), we know it’s a necessary part of a complete plan, and you should, too. Good luck out there today, and remember to keep in mind what you’ll do if it doesn’t all work out.

* Note that I have a deep visceral reaction to the word “cyber,” but it’s the word that has been thoroughly adopted in this discipline and so it has been used here for the sake of readability. The confusing image for this post is the inoculation to having to use the word.

I waited. And waited. My flight began to board. I was still on the other side of security. Finally, I went to the airline desk and told them what was going on, and they changed the name on the ticket to match the ID I had on hand. I made my flight. I’m not sure if the airline did a legal thing, so I’m not naming them, but holy shit am I grateful.

I waited. And waited. My flight began to board. I was still on the other side of security. Finally, I went to the airline desk and told them what was going on, and they changed the name on the ticket to match the ID I had on hand. I made my flight. I’m not sure if the airline did a legal thing, so I’m not naming them, but holy shit am I grateful.