I’ve long been interested in the question of how formal and informal groups interact in crisis. It is my proverbial jam, as no one ever says.

Basically, it boils down to this: official agencies are resourced and have predictable structures, but are slow and lack visibility to an affected population’s needs. Emergent groups in an affected region are by definition beyond their capacity to respond and are not trained in response, yet they have acute knowledge of their neighbors’ needs and can adapt to dynamic environments. While I’m still working on the long-form expression of these ideas, an opportunity to prototype an interface came up recently through the Naval Postgraduate School, Georgia Tech Research Institute, and a place called Camp Roberts.

Camp Roberts

There’s this decommissioned Air Force base near Paso Robles called Camp Roberts, where interoperability experiments are conducted quarterly. Only the engineers/implementers are invited to attend – no C-level folk, no sales. Each year, one of those four is focused on what the military calls “Humanitarian Assistance & Disaster Response” (HA/DR). I have some deeply mixed Feelings about the military being involved in this space. I respect my friends and cohorts who refuse outright to work with them. I see the military as an inevitable force to be reckoned with, and I’d rather take them into account and understand what they’re likely to be up to. Finding this place to plug different pieces of a response together without the sales folk or directors present, to actually test and play and fail is a glorious opportunity.

A Game

I’ve been working on the opportunity to build a game around a formal/informal interface for years as a way to explore how collaboration would fill gaps for these different actors. This project is called “Emergent Needs, Collaborative Assessment, & Plan Enactment,” or ENCAPE. The idea is this: both sides to that equation lack understanding of, and trust in, the other. A game could externalize some of the machinations and assumptions of each side, meaning a demystification; and creating things together often leads to trust building (that’s a reason why I’ve invested so much in makerspaces and hackathons over the years).

My informal friends were into it. So were my formal friends. But in order to know we could have any impact at all on organizational change, support had to be official from the formal sector. This took years (the formal sector is resourced but slow, yeah), but the pieces fell into place a couple months ago and the chance to build a game was born.

The People

It was of course vital that a wide range of viewpoints be represented, so the call was broad, but still to folk I knew would bring their whole Selves, be able to trust each other, and would be interested in the results of the game research. Folk from informal response, official agencies, nonprofits, and private sector were all invited. In the end, were were joined by Joe, Galit, Drew, Katie, Wafaa, John, Seamus, and Conor. Thank you all for taking time for this.

What We Did

We actually ended up meeting in San Francisco for our 3-day workshop for hilarious reasons I’ll disclose in private sometime.

On Sunday night, some of us got together to get to know each other over beverages and stories.

On Monday, we went through a Universe of Topics and visualized the workflows for our various user types. I did one for the Digital Humanitarian Network, Wafaa did one for Meedan’s translation and verification services, Katie covered a concerned citizen, etc. What were our pain points? Could we solve them for each other? We overlapped those workflows and talked about common factors across them. Different personas have access to different levels of trust, finances, and attention. They use those to build capacity, connections, and decision-making power. How could we use these common factors to build a game? How could we explore the value of collaboration between different personas?

Drew took this

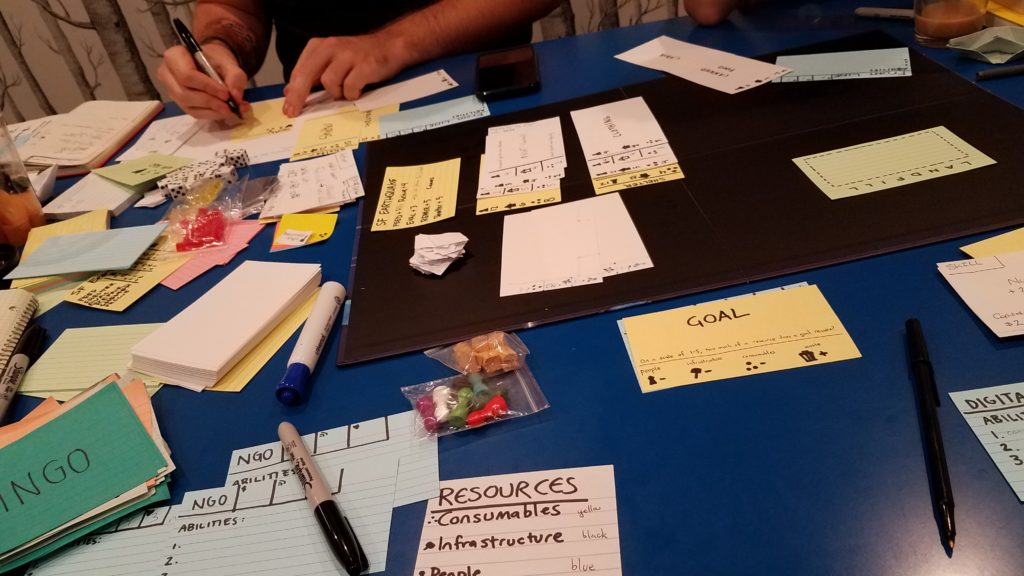

On Tuesday, we reconvened and started the day off with a game: Pandemic. This got us thinking about game mechanics, emergent complexity based on simple rules, and how to streamline our game. Individuals presented on what their game might look like, if left to their own devices. We explored combining the most compelling parts of those games, and started a prototype to playtest. It ended up being a counting game. Hm. That can’t be right.

On Wednesday, we drew through what the game play might look like and troubleshot around this shared understanding. It was closer to modeling reality, but still took some counting. We drafted it out to playtest, narrated through parts which didn’t yet make sense, and took notes on where we could improve. The last bit of the day was getting a start on documentation of the game process, on the workshop process, and on starting some language to describe the game.

We’ve since continued cleaning up the documentation and refining the game process. And so dear readers, I’m excited to tell you about how this game works, how you can play, and how you can (please) help improve it even more. Continue reading

We’ve since continued cleaning up the documentation and refining the game process. And so dear readers, I’m excited to tell you about how this game works, how you can play, and how you can (please) help improve it even more. Continue reading