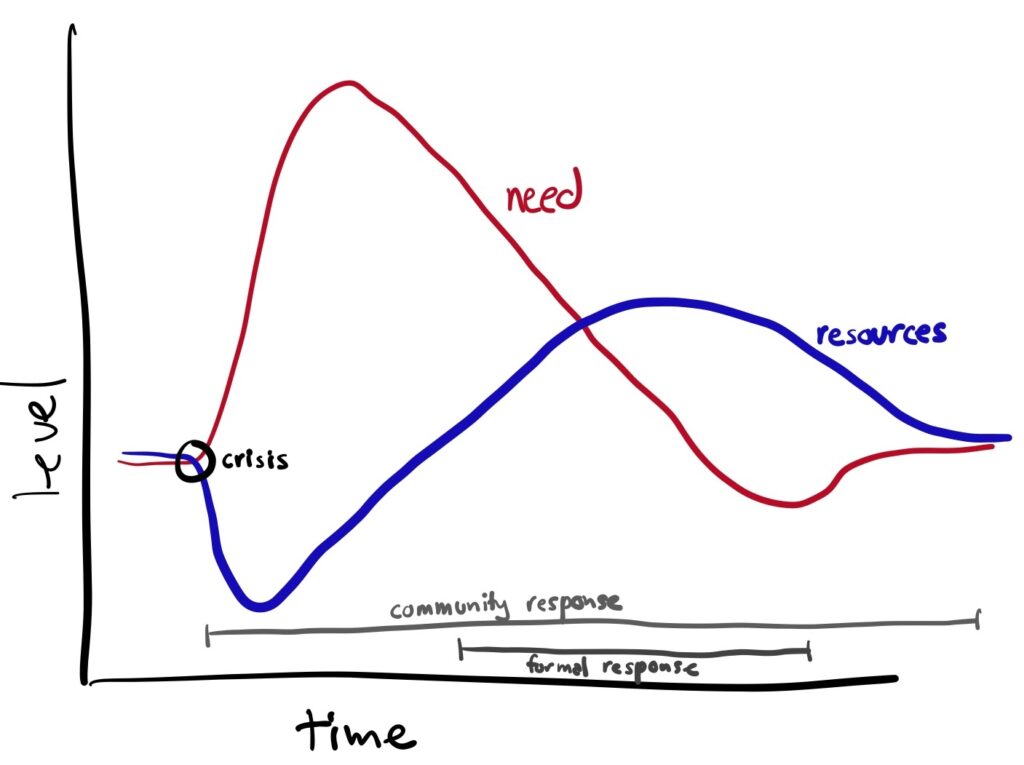

As some of you know, I have cared about crisis response for a long time. And now, as a side project, as furthered recently at my birthday conference, I’m working on a guide for the formal sector to interact with the informal. I’m also starting work on a zine for informal groups to know what’s up in times of crisis. The informal groups are harder to reach as you don’t know who they are in advance, and so our goal is to make this zine something the formal sector is willing to hand off, something that is findable online, and something that activist groups might seek out themselves in advance.

I’m really excited about it, but it’s also a LOT of work. And I’m not the only person with writing or artistry skills out there, so I’d like to use this as an opportunity to commission some work. There’s a form at the bottom of this blog post to sign up for a section if you’re interested. What follows immediately are short write-ups of areas I think need better words and/or a piece of art to express.

Basics of response

Reviewing in an informal way things about WASH and food safety, plus common sense for physical safety for collapsed buildings (unit 7) etc. Slow is smooth and smooth is fast, it’s worth moving carefully. Would require some independent research to figure out what is being detailed by official sources.

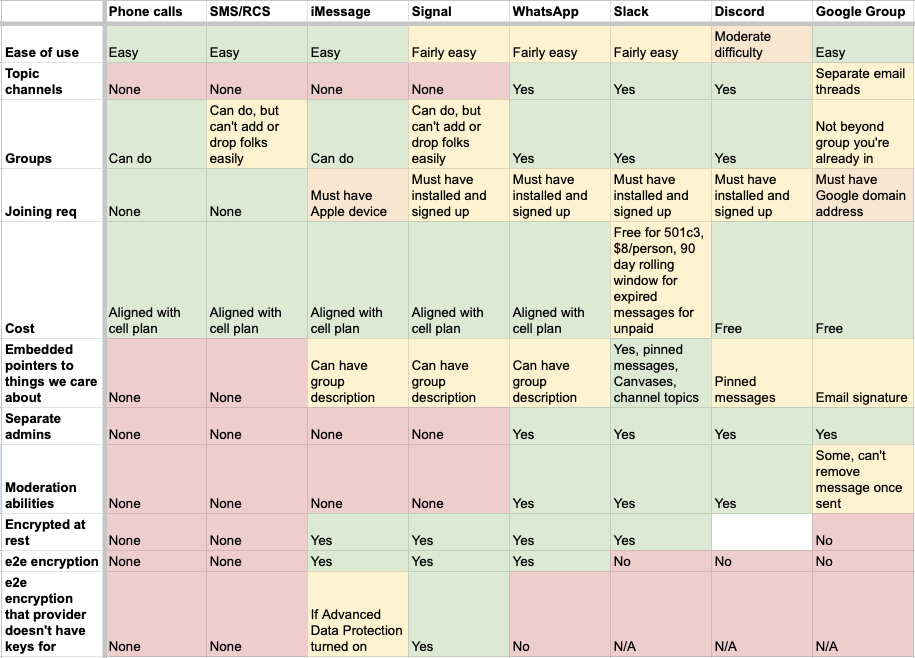

Data safety

You’ll be setting up some basic things immediately – a place to chat (mailing list, Signal group, etc) and a place to store information (wiki, Google Drive, etc). When a crisis first kicks off, data is gathered fast and loose, and access is given to anyone who might be able to help. That is expected and we get it. However, after time wears on and things stabilize a bit, some thought needs to be given to data retention and security, including who has access to what.

Limit how many administrators you have. Use secure-enough tools, limit who has access, send over encrypted channels. Retrofitting is a pain, but is worth the pain. Do your best in the moment, without sacrificing efficacy.

This would be a conversation we have to flesh out details you might be interested in and to highlight what I think is important and reasonable here.

Sustainability & leadership

At odds with a do-acracy, it makes more sense to select each other for leadership positions. Be wary of narcissism, usually indicated by someone wanting full ownership of something. Quiet, competent leaders are great in American cultures. This is something for conversation if you don’t already have a background here.

Self and community care

Support your leaders, IE if they’re a single parent, get them child care support while they coordinate. Taking at least one day off a week is necessary. You cannot go all out indefinitely, and your work will suffer if you try to. Rotation of duties is an excellent way to build resilience of responsibility in your community and to strengthen things by knowledge sharing. Feeding the group is important work. Etc. This would be great for someone passionate about governance structures and self care. Happy to have conversations about this and the sub topics to deepen the thinking here, but if you’re already familiar with self organizing structures, you’ll have a great start.

Documentation

Documentation often seems like the BIGGEST waste of time, but it is SO important. It will help you with handoff to other people (sustainability), it will help you communicate and coordinate with other groups (impact), and it will help you tell your story later (learning). Share outward as much and as often as you can handle, it will help everyone, and they in turn can help you.

A documentarian can be see as an apprentice to a role, writing down what they’ll do as they learn about it. This builds resilience in your group in multiple ways.

Happy to have a conversation about this one, but if you already love libraries and/or wikis, you’re probably set here.

Dealing with money

Eventually, someone will probably want to give you money, or you’ll start running into ways that you’d like to get money to spend on certain things rather than always coordinating material goods directly. Some groups, like Occupy Sandy, just estimate that they’d like 10% to fraud and that it would cost 15% in overhead to track, and so just gave away cash to projects based on donations flowing in. Other groups, like Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team, ended up forming a 501c3 so they could better accept funds to pay for people’s airline tickets. Each comes with risks and benefits. This would be a conversation with me and some other folks to get you set up on models and information.

Failure modes

Formalizing your group in different ways (often done to deal with the money problem) leads to different types of failure. People who form businesses (disaster capitalism) usually end up failing as a business because they thought their one-off crisis lessons applied everywhere else. Right-wing response groups over optimize for centralizing power, especially when things are going sideways, which leads to bits of the group breaking off to do their own things. Leftist response groups fail to build consensus around the next actions to take and dissolve. A conversation can be had here.

Some tips for interacting successfully with the formal sector

Like it or not, the formal sector is probably going to show up at some point and try to deploy to your area. Here are things to know about how they work and what they expect that can help everything run more smoothly. I’d write the intro to this section, but the subsections can all be conversations if they’re not clear enough already.

Have a person the formal sector can talk to

A broker liaison could be someone who has done CERT training or that otherwise has worked within a command structure before. They should be open to understanding where the formal groups are coming from, but firm in what will and won’t be accepted by the community. They will need to be available for lots of informational meetings. This is how the formal sector thinks of these folks. If someone wants to prepare for this in advance, FEMA’s independent study is great.

Flying drones

Drones are a really great way of checking out your area to see what is going on. However, if any planes are up in the air, the drones have to come down. Low flying planes are used to take photography for damage assessments to see where resources should be sent, as well as being used occasionally to deliver supplies, so they’re an important part of response and shouldn’t be interfered with (unless you’re in an adversarial environment).

Rule of thumb

If there is a SERIOUS safety issue, like a hazardous spill, if you cannot cover the entire area from view while holding up your thumb, you are too close.

Where and how your formal sector colleagues can talk with you

Formal entities can (and should!) be held accountable for decisions they make and actions they take. This means all communication has to be audit-able, which means they can’t talk to you on something like Signal. Their systems are also often locked down so they can’t install the latest and greatest new collaboration tool. Being willing to join them where they’re at (if they can get you an account) and/or to find new third places is a key component to opening up communication.

Interested in helping out?

Interested? Here’s a form to fill out to indicate interest! I’d love to see responses in by July 22nd. When estimating, please be kind to yourself, but while I’m making Bay Area money (NOT software engineer money), I also have a kid and stuff. I have worked as a contracting artist before and will limit myself to 2 revision rounds on each thing. You will absolutely be credited in the zine. You’re welcome to reach out to willow dot be el zero zero at gmail if you have any questions or want to see how progress is going.