Last weekend RecoveryCon happened, a distributed conference to examine how we can come out of this pandemic better than we were before. A blog post on how the facilitation happened already got posted, and now that the participants have approved the notes for public viewing, here they are, followed also by our Joy Gallery (things that are bringing us joy right now).

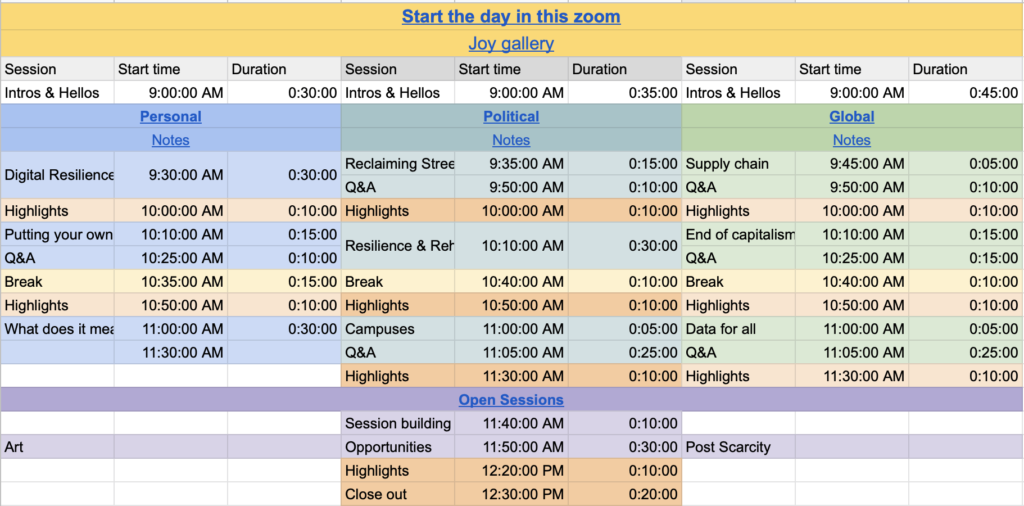

Sessions

These are very rough notes from session report-outs, linking to the track’s notes doc.

Supply chain: How we can organize the supply chain for emergencies. What’s going wrong right now, how it can get better. Anarchist organizations and organizing. Challenges of adoption and disseminating information to get people to use the system. Mechanisms that have prevented organizations from centralizing too much power.

Resilient organizations: gentler with ourselves and each other. This is unprecedented, we’re communicating differently. Internalize, feel it, express. How different organizations are trying to adapt. Yearning to connect, be of service. Not everyone is online. Social innovation, getting through the day. Invitation as a way to communicate. Going from community to life organizing and coaching.

Reclaiming streets: How our streets are changed right now, how to sustain those places. Not just pipes to get places. Less use of public transit from this pandemic but bikes as key. Political will to keep this momentum up. How can we take these experiments and make them more human scale, open to all, plan and build?

Putting your own mask on first: Make spaces meet basic need. Shit, sleep, eat. Many people are relocating right now which is not great. Get a bathroom, bedroom, and kitchen into a reasonable state. Bathrooms often only place you can be alone and vulnerable. These spaces are important. Change concept of success – instead of “hit these things or you’ve failed” – but instead “what is the smallest increment on the way to a goal you can be proud of? Cultivating joy and satisfaction.

Resilience & Rehabilitation: Incarceration, systems and narratives in place that are very broken. Are the majority of people in the state system convicted of violent crimes? Internalized the narrative of what the system is and who’s in it, why and how they’re there, what should happen after. Parole is really social death, people go back to prison because of parole violations not because of committing another crime. Showed a video clip. And interventions of restorative and transformative justice. Focus on healing process for survivors.

End of capitalism: Weird, deadly time we’re in. Need to look at new models already out there for a global context. US, UK are grappling with things that aren’t new. Patterns from elsewhere in the world. Think about transfers in one direction, need to go in other directions as well. Imagine alternatives. How do we change incentives? Challenge false dichotomies. Cooperative buy-outs.

How are we collaborative?: How we’ve collaborated during this time. Moving collaboration entirely online, better than half on half off. Not having to travel but still having access. Challenges of everything being online. Divide between digital and non digital conversation. Everyone has to contribute. If there’s a digital divide it’s difficult. STructure so everyone can participate. How things can improve: siloed and fragmented, lots of work within single communities. Conferences like this help, but not clear how this scales. How do we get the right people to talk at the right time?

Campuses: Many US campuses on path to closure. Physical space, use for space that is changing and not what the market structures would deem. Could we build with intention and in community? Concepts of education, pulling away from a system that encourages disparity. Experiences to the table. Book recommendations. Paths forward to making and taking space, like squatters’ rights. Fighting entrenched class structures. How to not need to feel productive at all times.

Data for all: Questioning assumption that data is record of record, faithful construction of reality. Constructed, produced. Produced in all types of new ways we don’t know the repercussions of. Dominant narrative of data generating new insights and how to meet those needs, but also new ways for data to control us without our consent. Concentrated interests extracting value out of us and our systems. Even when I’m presented with a request for consent, I don’t know, don’t have a meaningful way to opt out. Our paradigm of more data should shift from individual consent to harm reduction. Do we need new kinds of institutions to mediate these discussions?

What art is giving you visions for the future you want? How can creativity be part of future-crafting? Ways art can bring our imaginations closer to what another world could look like. Star Trek, UKL. Art in community, collaborative process being deeply fueling, esp with other collaborative processes. Meaning making and community building of having a physical object. Street art as assertion of people in space. Dystopian art as highlighting or telling us what we want to avoid?

Fun, creative, and inspiring opportunities for the future of [digital] communications/socializing more vulnerable populations participating. Rope people into ways we want to connect online. Serendipity of real world is missing. Town Online is trying to mimic that, but not really there yet. How we can get to conversations, like rooms for conversations like a house. Brackets and multithreading in chats to track topics. Using video chat with shared activity without expectation of eye contact. How to emote with avatars? Changing video call backgrounds as framing conversations. Annotation as something everyone can contribute to

How do we plan for a post-scarcity society within a society that is collapsing? What is hope? Redefining hope, going from this model of “everything will be ok in a few months” versus what I can have hope in today. Changes expectations and outputs of what you’re capable of. Prepper talk. Differences based on environment, and who is around. Unevenness of post scarcity. How unevenly distributed these crises are. We’ve seen alternative systems of sharing value, but it happens at small scales and in homogeneous places. I believe other worlds are possible, but I don’t see a path towards the multicultural world I want to live in. Security in a world of collapse feels bubbly.

We were all scared to show up. There’s not a lot of capacity to do things, including for the organizers and facilitators. But we’re glad we did.

Joy Gallery

- Bookcases! Lots of bookcases: https://twitter.com/BCredibility/

- Old Oakland Railways –

- See also https://ivansigal.net/kcr/

- Gardening. And the badgers.

- Listening to the wind in the trees

- Putting a sprig of rosemary or lavender in my mask as I talk a walk in nature

- sunset on the rooftop (I’m trying to make a ritual of it)

- Micro moments to fill in

- Vicarious cat interactions through lots of videos/tiktok compilations

- Seeing people’s rooms/homes in the backgrounds and getting to know them in that way

- This piñata head:

- This piñata head:

- The poetry of Keetje Kuipers (example)

- Somehow ended up in an all canadian group

- Playing scrabble with my best friends – i have won 1 game of 700. Keep on

- Art – making beauty out of struggle

- Convening spaces for community across the world – humanitarian wise. It is hard but people really appreciate it

- Reconnecting with old friends, virtual hangouts

- These Twitter threads:https://twitter.com/kylosbarechest/status/1264208265245683712

- https://twitter.com/vilruse/status/1263891922168545281

- I (Zephyr) have been putting out a small newsletter every Friday of only good/cute/queer/hopeful things – https://tinyletter.com/zalsoa

- MINECRAFT (building huge group projects with friends)

- Being with my son

- Being able to enjoy my art installment around my nome Meural

- Reconnecting, finding my grounding and sense of place

- Being outside, hiking, connecting with my friends

What’s bringing you joy right now?