While I was at Truss, I helped move us from a dozen people in the Bay Area to nearly a hundred across 20 states. Through monthly meetings to run experiments in improving our practices, we came up with the Distributed Playbook. It’s since changed format enough that I missed the original version, so I’ve ported it over from Github to a page on this blog. It, along with the onboarding guide, are two of the things of which I’m most proud from my time at Truss. Hope they can help you out, too!

Category Archives: Truss

Onboarding documentation the most important documentation

Originally posted on the Truss blog

Most of us rely on documentation in one way or another. In this blog post, we attempt to make the following points:

- Most documentation should be treated as if it is onboarding someone to an organization, project, process, etc.

- Involving multiple people of different practice areas increases the quality and context of the documentation.

- Documentation can help a growing/large organization stay in sync with itself.

- Truss’s onboarding documentation is great and you should check it out.

Onboarding documentation is the most important documentation

“Documentation” is the media object (text, video, images, etc) which explains how to do something. Docs can take the form of descriptive policy, READMEs, How-Tos, welcoming, etc.

Documentation is nearly always worth having, but if you only have time to get one piece of documentation in place, it should be made on the assumption it’s being used to onboard someone to the project, organization, process, etc to which it relates. A person rarely looks at the whole project, organization, process, etc as a whole as that is overwhelming. They instead look for signposts that provide context and support in understanding the system they’re about to interact with.

When I got started at Truss long long ago in 2017, we had an onboarding manager checklist but no real guidance for the new Trussel outside of that human contact. Ari, who at the time was doing onboarding (and is now an engineer), is an incredibly high-touch, welcoming human. However, if she or another person helping with the process had a more pressing thing to be doing (which was often the case at a suddenly and rapidly growing consultancy), a new Trussel would stall out and be left in a sea of tasks, new tools, and new people, with a sense of “what even do I do?” And when one doesn’t have a clear path forward, one can feel useless, which is not a good feeling when you’re just getting started somewhere and want to prove your worth.

This was because we had documentation about how things worked, but not from the perspective of the person being onboarded to the organization. If we were to get this in place, a new Trussel would feel more welcomed and solid in their footing.

Luckily(?) I compulsively document things. So as I learned about bits and pieces of the organization, I wrote down in one place what others should also expect as they came in. Oh, we do have a document about PTO? Link it up and give a quick summary. We don’t have one on role definition? Could I help make one? I tried to set it up so when something was unclear or incorrect in the docs, a new person would feel safe enough to ask questions and empowered enough to edit the docs when they learned the answer. This generated a surprisingly long document which was complete enough, but also incredibly overwhelming.

Pouring the firehose into drinkable cups

Documentation takes a bunch of different people of different practices to make it good. Sharing the load also makes creating and maintaining the docs a lighter lift and a shared source of truth and object worth maintaining together.

Our document was way too burdensome, so we called on our design content strategists James and Kaleigh, who suggested it be reformatted into phases of onboarding time. Delivery Manager Amy tried this format out first on her project, and then I expanded it into the MilMove project. When it stuck well enough, we did a card sorting exercise for who wanted to know about which parts of our operations, and when it made sense to learn about them. We also started linking out to external documents when a section got too long or convoluted. This allows people to focus on the big picture, and dive in deeper when something is relevant to them. Then we took our honking document and rearranged it and edited it down to a mere 28 pages.

Just as people had started asking to have new policy or reference docs put into the emerging guide, everyone also helped edit for clarity. It became a thing for more folk to reference and make use of. And just as Nelz, Jeri, Andrew (all engineers), and Mallory (designer) have held my hand in multiple ways to migrate the Guide from a Google Doc to GitHub Pages, many other folk have also refined the Guide to make it what it is. Including our general counsel Burstein writing the best damn disclaimer you ever did see and otherwise making sure we’re not just witty but also reasonable legally.

We have all done this in the spirit of being a warm, welcoming place for new Trussels. All those folk named here (and those I have forgotten 💔) have demonstrated our values in order to make it an easier transition for others to also represent those values.

If you are working on onboarding documents, call in help! Ask tenured folk to verify knowledge is represented, newer folk that it’s clear, content specialists to review structure, etc.

Being able to document something requires understanding it

Growing and large organizations are often accused of “the left hand not knowing what the right is doing.” This has to do with the functions of the different hands not being clear to the other. Enter (you guessed it): onboarding documentation! By describing how different components of a system work, the system itself has opportunities to become more aligned.

One thing that came up time and time again as we worked on the Trussels’ Guide were points of inconsistency or lack of clarity around internal workings. As we grew from 14 to 90 Trussels during the development of the Guide, our processes were also scaling. We became more robust and more formal. But importantly, we always did so with an eye to being comprehensible to an incoming Trussel. Docs shouldn’t only be intelligible in the context of the whole — each should stand on its own in a meaningful way. While most Trussels can’t (and shouldn’t have to) know about every tiny detail of how the business operates, they should be able to look up the details and/or who to ask if they start to care.

As an aside, there’s also this great piece about how you can’t fix a product (or a process) by having good words. The thing you’re describing has to be good, too.

Documenting can surface where things are out of alignment and provide a route to bringing them back into sync with each other. This is important for your organization, project, or process to be functional within the context of itself and the larger systems of which it is part.

A quick how-to

What’s worth documenting? I start documenting when roughly three people ask me the same sort of question. Rather than respond to each separately, I

- try to write it down with the first’s help,

- talk through it with the second, and

- ask the third to try to self-serve with the document created.

This allows emergent areas of interest, guided by our new Trussels, to determine some of the aspects of the business we next define more clearly.

We’re proud of how we do things at Truss and want to share them

So now we are ready, dear reader, to show you how we work at Truss and, as importantly, how we talk about how we work. And so I introduce to you the Trussels’ Guide to Truss. In it are the ways we are kind to each other, how the business functions, some of the decisions we’ve made, and how we embed assumptions into our work.

We hope you’ll have a look, take what works for you, leave what doesn’t, and continue to engage in the conversation of how to build great businesses together. Also, if this seems like the place for you, we’re hiring!

A playbook for distributed teams

Originally posted on the Truss blog

There are a lot of articles coming out these days about how to be an effective distributed employee. But there is much less around on how to be a good distributed team. Truss hired our first distributed employees back in January of 2018, and we’re now at 55% outside our “home state” of California (and many of us are spread across CA). We’re now 75 folk, and there are usually 5 of us in “the office.” As Isaac recently said, “it’s like a coworking space that only Trussels have access to.”

We’ve had to learn a few things in order to keep the organization functioning and aligned with our values. We’ve now codified the steadiest of these lessons in a distributed playbook on GitHub.

A quick note on language, and why we chose “distributed” over “remote.”

“Remote” suggests that there is a central place to which a node is remote. Because we wanted to emphasize that we are all on equal footing, we instead chose “distributed” – there is no “center.” We have collections of Trussels in NYC, Atlanta, Chicago, Sacramento, LA, and SF; as well as individual Trussels in many other locations.

What the playbook holds

We think healthy distributed team interaction falls into four buckets: facilitating interaction, properly resourcing people, bonding with each other, and seeing each other in person on occasion. This includes other things like taking stack, having a place for banter, having offsites, and having ways to connect about not-work. Things we’ve talked about in previous blog posts and will continue to post about (and now will collect into this playbook as we do).

A quick note on internal references in the playbook

We talk in the playbook about TDRs – Truss Decision Records. We pulled these from ADRs (Architectural Decision Records) which we use in our code repos to document why we made certain choices. We do the same for our organization now, and anyone can propose a new decision. We should probably do another blog post on that at some point.

We want your help!

We’re still learning about distributed team interactions—we all are—and we’d love your feedback and contributions to the playbook so we can all learn with each other.

Facilitating distributed All Hands meetings

Originally posted on the Truss blog

All hands meetings are important – they are a way to spread a message, a way for a team to get to know each other, and a way to move a decision making process forward. They are easy to do wrong—to hear something everyone already knows a thousand times over, to be unclear, or to be a jumbled mess without enough time to accomplish a goal. I’ve run the numbers of how much we pay for an all hands meeting (something I can do with internal salary transparency), and the cost is nothing to laugh at. So why do we have these meetings so often (at Truss, once a week), and how can we make sure we’re getting the most of them?

We see facilitation as the way to get the most out of a meeting like this. I’ll arbitrarily define “meeting facilitation” here as the act of deciding what you want to get out of a gathering, planning for, and then constructing and maintaining a space and flow to optimize for achieving that goal with a group of people. This is different from presentations—which are also useful—as a presentation is about the clear delivering of a message by one or a small group of people to another set of people. It is possible to facilitate a set of presentations, especially if there is Q&A at the end.

Facilitating distributed meetings

As we’ve talked about before, facilitation changes when you have a distributed group. And so as Truss noses up past 70 (and still growing) we’re hitting new facilitation challenges. As our client base grows, and our internal operations change, and fewer Trussels know each other well, what do we want out of our all hands meetings (that we call “Practitioners’,” or “Prac” for short), and how can we be sure we’re achieving those goals?

Skill share

We know we don’t have all the answers at Truss, and so we wanted to have the conversation about how to further improve our practices with a broader group of people. Four Trussels (Sara, MacRae, Isaac, and Willow) were joined by Emily of honeycomb.io, Pam of One Medical, Aaron of CivicActions, Liz of Public Lab, and Mike of an undisclosed media company to skill share. The all hands we facilitate run from groups of a handful to in the 70s. Some of us rotate facilitators, some of us hold that honor for a prolonged period. Some of us are fully remote, some of us are clumped into rooms in different locations.

While you can get into the details by watching the video or reading the notes, our main categories of interest fell into engagement & participation, meeting purpose, and who is remote versus who is in person. We had a few main takeaways that we’ll be cross-pollinating across our organizations.

Facilitation Guild

Having a group of similarly dedicated folk within your organization can help up everyone’s game. Try out experiments together, lean on each other for support, and perform course corrections by having allies to check in with. We try out new things on our project teams and then share them back to the guild, helping the whole organization benefit from gains (and avoid and/or reproduce discovered failures!)

Collaborative decision making

While some of us (including Truss) still use all hands primarily as a way to disseminate information, Aaron of CivicActions and Liz of Public Lab told stories of making decisions as organizations during all hands meetings. This makes my robot heart sing with joy, and the Truss facilitation guild will be looking for ways to start doing this in our projects.

“Hand” in chat

As a group grows larger, it becomes more difficult to track who wants to say something, and in what order. We use the video conferencing software’s chat to raise a hand through text—literally typing “hand”—in order to signal we want to say something. Not only does it help the facilitator keep stack, it also gives time to folks who want to consider what they want to say before they say it

Banter / Side channel

Banter is a great way to keep everyone engaged—I may not want to take up everyone’s attention with the perfect gif in reaction to something that’s just been said, but if I have somewhere to post it, I’m more likely to stay engaged as are the folk looking at and responding to the gif. Using a side channel (so not distracting from the “hand” channel above) means everyone wins.

What’s next?

Huge shout out to all the folk who joined for this facilitation skill share—I’m excited about a lot I get to do, and this was still the highlight of my month thus far. To be able to share skills across organizations is rarer than I’d like in the private sector, and that’s just silly. We all do better when we all do better. I hope we have more reason to collaborate with each other to grow and uplift the spaces we’re in. Is there something you want to learn or share about?

There is a growing body of work around working from home and working from anywhere… as well as the practices individuals take to stay sane and healthy while doing so. But we’re lacking a supporting body of work in how to help groups work together well in this new distributed environment. Truss is beginning to codify our learnings into a distributed playbook, which we’ll share when it’s good enough to face the tumult of the internet. When it’s out, we hope you’ll join us in making it better.

Upping Our Distributed Practices

Originally posted on the Truss blog

While there are lively debates about whether or not the Future is Distributed, at Truss we’re having a pretty solid time of it. Running online meetings is just the beginning of making sure your distributed team is included, and we’re continually working to improve our distributed practices.

We have a running doc of practices we want to try. Our goal is to fail at least occasionally — it means we’re actually reaching further than our grasp. Here are a handful that we’ve recently tried, and to what result.

- Persistent distributed video : quiet failure

- Being Humans Together : resounding success

- #in-out-status : success

- Synchronized cupcake delivery : failed, but worth a re-attempt

Persistent distributed video

One of the things we missed most in becoming fully distributed was the human bonding time we got with our rad coworkers while in the office together. One of our attempts at addressing this has been a standing video link which people can jump into and out of to “cowork” with each other. There’s sometimes some idle chitchat, and then often heads-down working.

It ended up not working for a few reasons:

- being on it as the same time as other folk is rare;

- we have a culture of scheduling time to talk about specific subjects rather than hoping it happens organically;

- the standing video link quickly became “invisible.”

Result : quiet failure

Being Humans Together

Getting distributed folk in a video in a coordinated way to talk about Not Work is now a standing half-hour weekly timeslot. It is some Trussels’ favorite part of the week. We do a couple different formats:

- if under 9 participants, each person gets 2 minutes to talk about anything at all they want to, so long as it’s not work.

- if it’s more than 9 participants, a quick checkin happens on how people are feeling, and then breakout groups of 3-4 people each for a deeper dive.

We sometimes have a prompt (“what’s one story about you that you think really represents what you’re like?” or a show-and-tell.

Breakout functionality in video conferencing software has been amazingly useful. So far we’ve done these randomly, but at some point we might try self-selection into these “rooms.”

Result : resounding success

#in-out-status

Has this ever happened to you? You log in on the East Coast after a sick day, and you have no. idea. what is going on with different stories. Did someone delete that blocker, or has it been worked around? And it’s 3 hours before anyone else who might know what’s going on will be online.

We now have a Slack channel called #in-out-status where people give a brief summary of the status of what they were working on before they go out for the day. It’s evolved to be a place where we also flag when we’re in for the day, going to lunch, taking a sick day, etc.

Result : success

Synchronized Cupcake Delivery

The project I manage recently hit a big milestone in October. While it was more of a non-event than our June release, there was still some stress around it, and a celebration was warranted. I set up a 2-hour session — the first hour of which was to catch up with each other (similar to Being Humans Together, but less structured), and a second hour to wander around where each of us is, and post pictures back to the group. The pictures were to put everyone on equal footing, rather than prioritizing office Trussels.

Also, during the first hour, I had lined up (what I thought would be) synchronized treat delivery to people regardless of location, scheduling deliveries for the time of the zone of delivery (IE, deliveries marked for 11:30 PT, 13:30 CT, and 14:30 ET in the interface should all arrive at the same point in time).

It ends up this is not a use case for this particular delivery service.

While all the cupcakes (plus one cookie order and one bundt cake order for some destitute places of the world which don’t have cupcakes available for delivery) for people in my timezone arrived as expected, 2 folk received theirs at the time requested but in MY timezone (hours late), and 2 received theirs hours early (for conversion errors I don’t understand).

While it didn’t work out this time, everyone felt included and celebrated. Definitely worth trying again at some point.

Result : failed, but worth a re-attempt

When Things Go Wrong: Response and Recovery

Originally posted on the Truss blog

When building systems with threats in mind, it’s not enough to just plan, not enough to just raise the cost to a bad thing happening — we still have to have an idea of what we’ll do when the bad thing happens despite our best efforts.

Truss modernizes government and scales industry through digital infrastructure. Information which is sensitive to individuals and to the welfare of the organization flows through the pipes we set up. Whether hospital records, the move locations of a military family, or financial data, Truss takes the best care possible in setting up infrastructure which mitigates the likelihood of a breach. We also have a plan for such a breach, in case it happens anyway.

At RightsCon, I moderated the panel The Rules of Cyberwarfare: Connecting a Tradition of Just War, Attribution, and Modern Cyberoffensives with Tarah Wheeler, Tom Cross, and Ari Schwartz. The question was this: if “cyber”* is a fifth arena of war (the existing domains being land, air, water, and space) what is a just response to a cyberattack which follows the international expectation of deescalating?

The panel and audience knew that the responses which are happening now — the assumption of “hack back” against other state adversaries, the use of CFAA against people who might otherwise entertain the thought of being a patriotic hacker — we don’t agree with. The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) is what makes breaking those terms of service that are too long and dense to read fully a federal crime. That’s right, logging into your partner’s bank account after their death in order to pay the house’s electrical bill is a federal crime, and it’s the same law that’s used in most of the “hacker” cases you read about in the news. It’s also the number one reason the infosec professionals I know and love refuse to work with the government. The ACDC bill which allows “hacking back” is an exception to CFAA which means you can attack a computer that’s attacking you. Except of course it’s not that clear-cut.

Which brings in the questions that many folk in the audience had. What about attribution (the ability to know who is taking the action)? This is hard in digital space because it’s easy to attack something from behind someone else’s IP address. What about asymmetry (an imbalance between those in conflict with one another)? Is it ok if one country attacks the other in cyberspace when the other country is just beginning to get online? These are hard problems, but we can’t wait until they are solved to have conversations about responses. If you’re having a hard time moving on without those hard problems being “solved enough” first, you’re not alone – the audience also had a deeply difficult time with it.

But what would be acceptable? If there was a breach of military moving data, do you think it would be responded to differently than the malicious changing medical records? Do you think who the adversary is would matter? Does the immediate or the potential future impact on those involved matter more? Where is the line between war and espionage? We ended the panel with the a comparison to disaster response, so attendees would have a framing to continue the discussion.

Disaster response also focuses on preparedness (stockpiling water for the next Bay Area earthquake), response (digging our neighbors out of the rubble), and mitigation (enforcing building codes which make collapse in an earthquake less likely). We are terrible at recovery. When it’s time to rebuild, the money, attention, and volunteers have dried up. Huge swathes of Far Rockaway (2012) and New Orleans (2005) are still a wreck from hurricanes.

The same is true for online attacks — whether doxxing (the nonconsensual revealing of personal information) or DDoSing (a distributed denial of service attack is when many computers all pester your computer for a response, not allowing it to say anything). We spend so much attention on battening down the password hatches and doing incident response that most don’t think about what being whole again after an attack that might happen anyway looks like. And so much of infosec and government work is about trying to prevent the Bad Thing from ever happening. Plan A is to make a perfect system. But we must own up to Plan A rarely being the plan that works out. Don’t your contracts also have release clauses in them? Planning for worst case isn’t inviting calamity, it’s being pragmatic.

One of our engineers recently said, “I would rather throw away some work than have to be under a too-tight deadline later.” This was said as Plan A seemed less and less likely due to bureaucracy and too many moving parts. But Plans B and C were being procrastinated on by our government protective cover. Why? I see the cost of exploring options in government as high, with extremely limited resources to work with. This means all sorts of fragility and resources wasted putting out fires when Plan A didn’t work exactly as planned. A balance of ownership, accountability, and flexibility would have helped alleviate this difficult situation. Additionally, setting aside resources for recovering from inevitable failure helps the entire system be more robust.

While Truss doesn’t specialize in the actual recovery (there are firms and insurance providers who do focus on response and recovery plans), we know it’s a necessary part of a complete plan, and you should, too. Good luck out there today, and remember to keep in mind what you’ll do if it doesn’t all work out.

* Note that I have a deep visceral reaction to the word “cyber,” but it’s the word that has been thoroughly adopted in this discipline and so it has been used here for the sake of readability. The confusing image for this post is the inoculation to having to use the word.

Well Met: Equity by Hackathon Awards

Originally posted on the Truss blog

Hackathons are a way for a community to rally around a cause, to learn from each other, and to push collective work forward. Here’s some research on it. Hackathons are also about publicity and headhunting. Think about the last few hackathons you read about. The piece was probably about the winners. Hackathons are, in general, further the “one great man” narrative.

But feminist hackathons now exist. We wrote a paper on the 2014 Make the Breastpump Not Suck! Hackathon which was about exactly that. But one thing we didn’t get quite right in 2014 was awards.

So for the 2018 Make the Breastpump Not Suck Hackathon, we took a different approach. We made our objectives explicit and described how we would reach towards them by devising a strategy, putting that into a process, and then implementing. This post is about that journey.

Explicit Objectives

Awards are often used to reward the most “innovative” ideas. Prizes are often given out of the marketing budgets of businesses, based on the anticipated attention gained. In contrast, when I have given prizes at open access and disaster response events, I have focused on rewarding the things one’s brain doesn’t already give dopamine for – documentation, building on pre-existing work, tying up loose ends. Our goals for the MtBPNS award process were few, and at first glance could seem at odds with one another. We want to:

- encourage more, and more accessible, breast pumping options, especially for historically marginalized populations;

- support the burgeoning ecosystem around breast pumping by supporting the continuation of promising ideas, without assuming for- or nonprofit models; and

- recognize and celebrate difference and a multitude of approaches.

Slowing down

There’s also an implicit “f*ck it, ship it” mentality associated with hackathons. The goal is to get a bare-bones prototype which can be presented at the end. But combatting *supremacy culture and ceding power require that we slow down. So how do we do that during a weekend-long sprint?

What’s the road from our current reality to these objectives, with this constraint?

Devising a Strategy

Encouraging more options and supporting continuation assumes support through mentorship, attention, and pathways to funding. Each of these could be given as prizes. Celebrating difference assumes not putting those prizes as a hierarchy.

Non-hierarchical prizes

First and foremost, we decided upon not having a hierarchy to our prizes. We put a cap on the maximum value of awards offered, such that the prizes are more equal. And, unlike last time, we removed cash from the equation. While cash (especially for operating expenses) is a vital part of a project moving forward, it complicates things more than we were set up to handle, especially in immediately setting up a hierarchy of amount given.

Strategic metrics

Half of our judges focused on strategic movement towards our objectives, and the other half on pairing with specific prizes. The strategic judges worked with our own Willow as judging facilitator and the MtBNS team to devise a set of priming questions and scales along which to assess a project’s likelihood of furthering our collective goals. You can see where we ended up for overall criteria here.

Awards offered, and who offered them

The other half of the judges were associated with awards. Each award had additional, specific criteria, which are listed on the prizes page here. These judges advocated their pairing with teams where mutual benefit existed.

The process we thought we would do

Day 1

- Post criteria to participants on day 1

- Judges circulate to determine which teams they’d like to cover

- Map the room

- Judges flag the 10ish teams they want to work with

- Teams with many judges hoping to cover them are asked their preferences

- Run a matching algorithm by hand such that each team is covered by 2 award judges and 1 or 2 strategy judges. Each judge has ~5 teams to judge.

Day 2

We hosted a science fair rather than a series of presentations.

- Everyone answered against the strategic questions

- Judges associated with a prize also ranked for mutual benefit

- Discussion about equitable distribution

Award ceremony MC’d by Catherine. Each award announced by a strategy judge, and offered by the judge associated with the award.

Where it broke

The teams immediately flooded throughout the space, some of them merged, others dissipated. We couldn’t find everyone, and there’s no way judges could, either.

There’s no way a single judge could talk to the 40ish teams in the time we had between teams being solid enough to visit and a bit before closing circle. Also, each team being interrupted by 16 judges was untenable. The judges came to our check-in session 2 hours into this time period looking harried and like they hadn’t gotten their homework done on time. We laughed about how unworkable it was and devised a new process for moving forward.

Updates to the process

Asked teams to put a red marker on their table if they don’t want to be interrupted by judges, mentors, etc.

- Transitioned to team selection of awards.

- Made a form for a member of each team to fill out with their team name, locations, and the top three awards they were seeking.

- Judges indicated conflicts of interest and what teams they have visited so we can be sure all teams are covered by sufficient judges.

Leave the judging process during the science fair and deliberation the same.

And — it worked! We’ll announce the winners and reflections on the process later.

Well Met: The Online Meeting

Originally posted on the Truss blog

There are many valid reasons to consider having an online meeting — maybe your squad is spread across multiple time zones or just different regions, or maybe you’re trying to foster a time of inclusive change at your org. However, with that optimistic reach for cohesion comes some real risk: online meetings are, inevitably, much more difficult to do effectively than in-person ones.

These two meeting types do share some goals: not having a single talking head, needing to pay attention to the “room’s” temperature, needing an agenda and a dedication to timekeeping. What changes is that people are even more likely to be distracted and less likely to engage, reading a room is different, and audio/technical issues are exponentially more likely as more people join.

To host a successful online meeting, you’ll ideally have:

- an agenda;

- strong, uninterrupted connections for each attendee;

- a conferencing system that allows for “hand raising” or other signals;

- a place for notes to be taken collectively;

- someone whose sole task during the call is dealing with technical issues (at least until the system and participants are tried and true).

Adjusting your own expectations is also a useful exercise. I think of online meetings as a block of time everyone has offered to spend attention on the topic at hand… not that they’ve agreed to listen, nor (if they aren’t listening) to speak. Maybe I’ve simply admitted defeat too early.

How to be remote

When it makes sense

If anyone on your team is remote, everyone on the team should act remotely. Sometimes we have 4 or 5 people of a 6-person team in the same room but on laptops for a Truss meeting. We do this because the moment meetspace is prioritized is the moment you’re not able to hear your remote crew. They matter. That’s why they’re your crew. Invest in noise-cancelling headphones and a reliable conferencing system.

When you simply can’t all be online, have a person in the room dedicated to watching for signals from the online crew that they want to speak, can’t hear, have questions, etc.

Temperature checks

It’s harder to gauge how people are feeling during a meeting when it’s not in physical space. Are shoulders slumped because energy is low or because proper posture at a desk is hard? Are people looking away because social media truly is a fascinating cesspool, or because they’re displaying the video on their other screen? WHO KNOWS. Here are some ways to read a digital room.

- Optimize for how many people you can see at once. Zoom gallery mode works well for this. There’s even a special setting for sharing a screen on one screen and still having gallery mode on the other screen if you’re sufficiently decadent to have more than a single screen to work from.

- Be sure to check in on people you can’t see. People still call by phone to video sessions; that’s part of their beauty. But not seeing someone’s face means not only are their reactions not included in temperature checks, but also that sometimes we even forget they’re there. Make a conscious effort to include them.

- Set (and stick to) how people “raise their hands.” We often use the “raise hand” button in Zoom to help the facilitator keep stack. This is because, again, lack of physical bodies means a sudden lean into a camera might be someone getting comfortable, not wanting to jump into the conversation.

Some tools have options to use (or adapt to use) for polling, including Zoom and Maestro. These can be used for a multiple-choice question, for voting on if a proposal should pass, and for flagging technical issues.

Technical support

One of the most distracting and time-consuming aspects for the facilitator (thereby impacting everyone else on the call) is a participant experiencing technical difficulties. “Are they ok? Is it their setup or ours?” One of the easiest wins for online calls is to have a person dedicated to troubleshooting technical issues. While the facilitator moves the group towards the meeting goal, the troubleshooter can help everyone engage fully.

Agenda and what you ask of participants

Online meetings don’t have to be a time during which everyone half-listens-in while perusing parts of the internet with the other half of their attention (we’ve all done it). Your goal as facilitator is to offer opportunities for people to engage even when not fully listening to the speaker. Having other things related to the topic to work on assists in maintaining and regaining attention.

Collective note taking and asynchronous questions

In contrast to fully in-person meetings, where it’s reasonable (even vital) to ask people to put away their devices so their attention can be maintained, remote meetings take place on the distraction device. One of the best ways to keep people engaged is to ask for their help in documenting. Multiple people can take notes in one place, with others cleaning up typos or adding in links. This can evolve into a “live blog,” and/or will sometimes spark side conversations in nested bullet points. Both add depth and thoroughness to something that might otherwise be a bare-bones skeleton not much better than the agenda itself. Taking notes this way can lead to documentation like this.

Taking this approach also helps those who are joining late or having audio issues — they can follow along in the notes to catch up, or to read ideas they weren’t sure they heard correctly.

Breakout groups and other activities

Breakout groups and other activities can still happen when meeting online, it just takes a bit more planning and group robustness than doing it in person. Zoom and Maestro both have a breakout-room functionality, for instance, which allow you to randomly or directly assign people to rooms, to indicate when wrap-up times are nearing, and to regroup people. You might also set up jit.si or Google Hangout rooms in advance for breakouts, and include the links to the breakouts in your notes. Asking people to maintain documentation from these breakout sessions in the main set of notes ensures a cohesive understanding is still maintained across all groups.

Activities such as spectrograms can also be adapted to online space – when using collaborative note taking, put a grid into the space, like so, and then have people move their cursors if visible (Google Docs) or mark an “x” if highlighted by color code (etherdocs) based on where on the spectrum they “stand.”

We’d love to hear how you engage with folk in online meetings – it’s a growing art form, and we’re still wet behind the ears ourselves!

Well Met: Upping Your Facilitation Game

Originally posted to the Truss blog

We talk a fair amount on this blog about how to have better meetings. And we should! Taking the time for some meetings will save time over all… but it’s a delicate matter and one of great responsibility. But let’s say you feel like you get it. You’re the person charged with meetings going well, and you know which agile ceremonies are worth having regularly, how to determine other things worth discussing synchronously, and how to create and stick to an agenda. But you get it, and you’re hungry for more. This post should help you get here by:

- offering structure by which to share skills and…

- suggesting when to deviate from (or go without) an agenda.

By including better facilitation practices in more aspects of your work, group dynamics will improve overall and everyone can focus on the actual work at hand.

Skill Shares

The more team members in a room know how to facilitate, the easier the conversation can be. Two ways to increase capacity in your organization are by mentorship and encouraging behavior which allows a group to facilitate itself.

We already talked a bit about how to mentor other facilitators in Well Met: The Facilitator, but it merits a deeper dive. To mentor other facilitators, first look for the helpers. Ask folks who see others raising their hands, help get a conversation on track, etc to review agendas with you. If they’re interested in trying out facilitation, backchannel while they or you facilitate, and debrief afterwards.

To get a group to be better at facilitating itself, ask folks to cue the person who comes after them in stack. Then, encourage people to self-regulate for time and how many points they make (one of the “Rules of 1”). Finally, work to get folks to cede the floor to someone who has spoken less than they have, often by prompting a quieter person with a question.

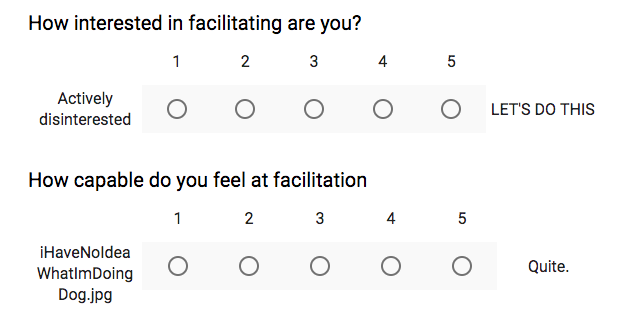

At Truss, we ran a quick 2-question survey to pair those interested in facilitating with those who already feel comfortable doing so. We stagger by skill level, so everyone has a chance to be in both a supporting and lead role.

We are Very Serious People.

When to deviate from the agenda

In Well Met: The Meeting Itself, we talked about how to create an agenda and then facilitate from that arena. This is an important and useful thing to do for a good long while, if not indefinitely. However, if you find yourself thinking “oh, I know what would totally work better instead!” and you’ve built trust with the group, it’s time to deviate.

My agendas, while well planned, often get tossed out within 5 minutes of any meeting starting. It’s similar to agile practices in that way – the preceding research and planning gives a solid sense of what problems are being solved and awareness of the context; but flexibility to adapt (or throw out) a plan based on what is most needed in the moment of action to achieve those goals. Because you’ll have facilitated many different sessions at this point, and tried out a lot of different facilitation practices, your toolbox and skill will be substantial enough to try something that seems more appropriate in the moment than your plan.

Taking a self-assured, but mildly cavalier approach to this is one successful approach to getting group buy-in for these deviations. “Well, I thought we were going to do X, but now that’s not going to help us get where we need to be, so we’re going to do Y instead. Any concerns about that?” while making eye contact to assess before moving on works well. Also sometimes “Wow Past Me has some terrible ideas. We clearly don’t need this entire next section in order to achieve our goal. Let’s skip it and save some time, shall we?” This needs to always be coupled with a reminder of what the goal of the meeting is, to keep all conversations on track.

Sometimes, if sufficient trust has not been built up, people will take this opportunity to discuss how the discussion will happen. Time box this and move on when the time box is done.

Other times, in groups with a particularly high level of trust, I won’t even share my agenda, which gives me leeway to adapt without making excuses. That said, I will have absolutely made at least one agenda in advance.

Where we’re going we don’t need agendas

And then sometimes there’s so much confusion about a topic that the meeting itself is to resolve the confusion. In which case it’s highly unlikely you get to have a traditional agenda. If this is the case, have a solid sense of who needs to be there and how the conversation might start. You might discover other folks are needed partway through, or that someone could be using their time better elsewhere. Apply the “law of two feet” here and let folks leave if they’re not needed.

As your comfort in facilitation grows alongside your activity toolbox, your ability to adapt in the moment will likely increase. To gain the benefits of that increased skill, allow yourself more flexibility while building out a stronger overall capacity in your organization. By

- offering structure by which to share skills and

- suggesting when to deviate from an agenda,

group dynamics will improve overall and everyone can focus on the actual work at hand.

Well Met: The Facilitator

Originally posted to the Truss blog

We’ve all been in dead-end meetings. No matter how dedicated and efficient your team is, a few bad meetings can derail their productivity and, even worse, their morale. In the next post of our series on maximizing the value of meetings, we talk about one of the aspects of a good meeting: the facilitator.

Practice the techniques highlighted in this series to:

- increase the effectiveness of meetings;

- decrease the number and duration of meetings;

- build team cohesion;

- cross-pollinate information across teams; and

- do so in a way which leads to new insights otherwise left buried.

You’ve learned how to determine whether you need a meeting and how to prepare for and drive those meetings, now we highlight how we select for that facilitator.

Who does this?

It’s a lot to take on. Plotting a course for effective meetings means setting aside time to discern if a meeting is actually needed, preparing for it, and assigning a dedicated person to facilitate the meeting. An important thing to note is that facilitators will participate differently in in a meeting. Experienced facilitators have a responsibility to not add their editorial opinions, and beginners may have a hard time facilitating while also joining a conversation.

Project managers as facilitators

In Waterfall, big plans are defined, then staff are tasked with executing a predetermined set of requirements. Project managers are responsible for tracking if individuals or departments are meeting deadlines such that the entire Gantt Chart stays on track.

In lower-case-a-agile, we see the project manager as facilitator rather than task tracker. The project manager should be primarily focused on creating uninterrupted time for the team, while also keeping an eye out for when sharing information would make that working time even more effective. This means the project manager should already have an eye out for meetings that would benefit the team and guard against those that won’t (our first post in this series). The project manager should have their finger on the pulse of what folks are up to so much of the work for agenda prep is already done (our second post in this series). Because agile team members are entrusted with finding the best route to solving a given problem, the project manager’s goal is to open and maintain the space for meaningful conversations, which points to the facilitation aspect of useful meetings (also the second post).

In short, at Truss we are structured to put project managers in the best position to uphold the responsibilities put forth in this series. But it’s not just on them.

Increasing facilitation capacity in your org

Facilitation is a core component of being a servant leader. But just as with any attempt at organizational change, it’s difficult for a project manager to come in and implement all this. A nurturing environment cultivated by the leaders of the organization means facilitation as a skill can build up throughout the organization. For this reason, when a project manager is unavailable, we tend to lean toward someone with experience in facilitation, and who doesn’t have a personal stake in the meeting itself. This could be an engineering lead, design lead, product manager, business lead, or founder. They often have additional authority and responsibility to a client.

Project managers can’t (and shouldn’t) be in every meeting. Whether there are multiple meetings happening at once or it just doesn’t make sense for the project manager to attend, other folks in the organization should also be upping their own facilitation game through facilitation mentoring. Project managers can support this by guiding a mentee through the agenda-building process, backchanneling about facilitation practices, flagging issues during meetings where a mentee and facilitator are both present, and debriefing afterward about questions or concerns.

Why would I want to be a facilitator?

To do so helps everyone make equitable space for others, amplifying the voices that might otherwise go unheard and the fountain of good ideas which accompanies that.

It also makes meetings go that much more smoothly, as the team is thinking about how to be effective and inclusive while maintaining focus on the objective. Learning to watch for signals and respecting stack can be distributed across the group, which helps everyone manage themselves.

Read more about deciding when to have a meeting and how to prepare for and drive an effective meeting to have the full impact this series offers.

Why are we doing all this?

Bad meetings, like bad policies and negative environments, are tractable problems. By following the techniques highlighted here around determining when to have meetings, how to prepare for them, and how to facilitate, your meetings can be worth the context switching they require.

Good facilitation allows you to have fewer meetings, and the ones you do have will:

- be more impactful,

- be more effective,

- build team cohesion,

- and lead to new insights otherwise left buried.

You can help make it happen!