People don’t lean out of vehicles to ask for directions here, as they did in Nairobi. The security guards, when they exist, lounge in chairs and ask questions rather than standing, mostly silent, with automatic weapons. But like Nairobi, meetings can start (and end) hours late due to traffic, to tardy risers, to rain that causes traffic, to conversations running long, to torn-up infrastructure (that causes traffic), to slow service for your lunch meeting. Tardiness is sometimes used as a sort of posturing card to play – whether or not someone gives you a meeting, and how prompt they are, as sorts of indicators of status.

Everything we’ve done here has required status strutting in order to gain speed. Those plates I told you about? Only people with yellow plates get pulled at traffic stops, because they won’t be diplomats, or military, or donors, or government. If you get stopped, it’s easier for everyone if you just hand the officer money rather than pay the huge fine for driving illegally. Which most are. And because we don’t want to slow down our project, nearly every introduction is “and this is Willow, from MIT.” Which is great and all1, but as someone who prefers to be affiliated with institutions for access to incredible brains and the space to consider at length, rather than constructed legitimacy, it makes me feel like I’d be prettier if I just smiled2.

Those same posturings and rerouting the system means there’s a fear of transparency here. Entire systems here are built up around being opaque. People across all walks of life ignore the floods for fear of being blamed for what happened, being put out of a job. This means any transition into transparency will require safe space. No “we’re coming after you” attitude, but a “we have been operating to the best of our abilities within the structure we have. Now that the structure is changing, we get to change as well!” But it seems enough people into open data and transparency have done it with a vindictive streak that everyone balks these days, and it’s a slow, gentle process.

Two and a half days into an 8 day trip, we’d chatted with NGOs, World Bank3 employees, the Ministry of Water, UNHCR, and no people who actually live the experience this technology would change. And as much as I trust all of those people (and my hosts) to know what the status of their work is, I needed to go see things. Establish ground truth. Everyone gets caught up in paperwork, rhetoric, image, and email, and so seeing it for oneself is always imperative. Mark, an amazing guide and cohort as always, got us out to Tandale a full day early for the sake of my patience and sanity.

On the way there, Msilikale leaned forward to ask the bajaj driver to drive like he does, not like we’re tourists. The roads had washed out from the recent floods, full of pot holes and rubble to negotiate and lurch over. Tandale is a slum in Dar es Salaam, and is a place to live, just like anywhere else. We walk with a man who has lived there, him taking us past houses with water lines up to our mid-thigh, insides still covered in silt, to the river running by the open defication area (ODA here). Kids run by with make-shift toys, and young women peep out to ogle my hair (or Mark’s size)4. As we stand by a washed-out bridge, our guide explains context.

The river divides two areas, one has most of the markets and the other is mostly houses. There’s no grid system (it’s an informal settlement), and so paths are highly reliant upon available bridges, and new structures are based on those paths. IE, functionally ad hoc labyrinthine. And when the floods came, the bridge washed out, and there are still people learning about that and figuring out new routes home. No one is responsible for the bridge – the government won’t come fix it, and the man who built it and had lived nearby died awhile back. No one takes responsibility, either.

It’s not just the bridge getting washed out – it’s the height at which the water rose, and that the ODA is not much higher than the river on a regular basis anyway, and it’s certainly lower than the water marks. So all the trash and bodily functions and such from the ODA get caught up in the river, which means it gets clogged up (as do the drains in the area), which means standing water, which means more mosquitos, and mosquitos are bad news bears. That’s besides all the things in the ODA also flooding into the houses with the rest of the river water.

Flooded or not, the water from the river (and the wells around it) is used to wash, cook, and sometimes drink. This is only for people who can’t afford the water out of the water points – which can be salt or fresh. For half price, you can get jugs of salt water to wash with, and sometimes for cooking. For full price, you can get fresh water. The water is delivered out of water points – giant containers, raised up off the ground, from which people purchase water. These are privately owned, though installed and supplied by the government, and few enough are stocked and working at any given point that there are queues for the resource.

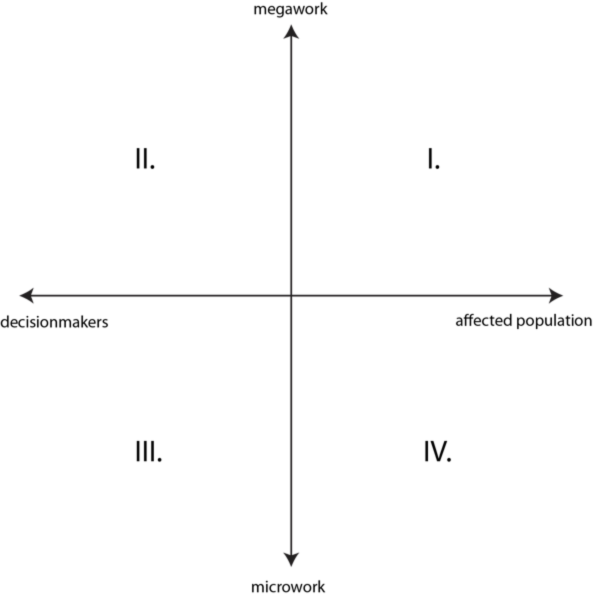

I ask questions. How do people know that one is broken? I wonder about where knowledge of what is going on would be hosted and shared. Is there a town center where things are posted, or is it all word of mouth? No center, just neighbors telling neighbors. No bulletin board system. I saw a vanishingly small number of feature phones while we were out. Only government and donor officials and contractors smart phones. Which, to me, makes me wonder how to get maps built of the water system back to the people in the area5. And given the level of corruption in the country, that data being only accessible to groups already in power is fraught with peril. Mark, aware to not ask questions about anything that won’t have a guaranteed resource response, waves me off asking more specific questions of how points break, and how to track response, what would next challenges and steps be, etc6.

I ask questions. How do people know that one is broken? I wonder about where knowledge of what is going on would be hosted and shared. Is there a town center where things are posted, or is it all word of mouth? No center, just neighbors telling neighbors. No bulletin board system. I saw a vanishingly small number of feature phones while we were out. Only government and donor officials and contractors smart phones. Which, to me, makes me wonder how to get maps built of the water system back to the people in the area5. And given the level of corruption in the country, that data being only accessible to groups already in power is fraught with peril. Mark, aware to not ask questions about anything that won’t have a guaranteed resource response, waves me off asking more specific questions of how points break, and how to track response, what would next challenges and steps be, etc6.

Night threatening and malaria mosquitos7 lazing about, we walk back towards the main road. At a bodaboda station, we negotiate with the fliers. I feel like I’m choosing who to be auctioned off to, having to dismiss the enthusiastic and be wary of the most aloof. Msilikale shoos off the most invasive, and I’m glad of a native Swahili speaker friend and a friend who’s 6’6”. That negotiated, we take a rather epic dive-bomb through traffic route home8, avoiding jams and vehicles traversing the median to gain a clearer route. Only one or two of the passing bike riders make kissy faces and eyebrows at me. Mosquitos die on my visor, and mud splashes on my boots.

And I stare at the bathtub in the hotel room, and think about not finishing my dinner when I was young and knowing most parents referred to starving children in Africa. But the issue then, and with this, is in supply chains and politics around them.

1. Waves MIT flag.

2. Institutional objectification. Which is at least different from institutionalized -isms.

3. Yes, of course I wore my “/capitalism” pin, why do you ask?

4. Please forgive my tense-shifting.

5. A core ethic when obtaining data. See also this blog entry.

6. DEMAND EQUITABLE ETC9

7. Dhengi for day, malaria for night.

8. Sorry, mom.

9. Inside joke.