Originally posted on the Truss blog

Hackathons are a way for a community to rally around a cause, to learn from each other, and to push collective work forward. Here’s some research on it. Hackathons are also about publicity and headhunting. Think about the last few hackathons you read about. The piece was probably about the winners. Hackathons are, in general, further the “one great man” narrative.

But feminist hackathons now exist. We wrote a paper on the 2014 Make the Breastpump Not Suck! Hackathon which was about exactly that. But one thing we didn’t get quite right in 2014 was awards.

So for the 2018 Make the Breastpump Not Suck Hackathon, we took a different approach. We made our objectives explicit and described how we would reach towards them by devising a strategy, putting that into a process, and then implementing. This post is about that journey.

Explicit Objectives

Awards are often used to reward the most “innovative” ideas. Prizes are often given out of the marketing budgets of businesses, based on the anticipated attention gained. In contrast, when I have given prizes at open access and disaster response events, I have focused on rewarding the things one’s brain doesn’t already give dopamine for – documentation, building on pre-existing work, tying up loose ends. Our goals for the MtBPNS award process were few, and at first glance could seem at odds with one another. We want to:

- encourage more, and more accessible, breast pumping options, especially for historically marginalized populations;

- support the burgeoning ecosystem around breast pumping by supporting the continuation of promising ideas, without assuming for- or nonprofit models; and

- recognize and celebrate difference and a multitude of approaches.

Slowing down

There’s also an implicit “f*ck it, ship it” mentality associated with hackathons. The goal is to get a bare-bones prototype which can be presented at the end. But combatting *supremacy culture and ceding power require that we slow down. So how do we do that during a weekend-long sprint?

What’s the road from our current reality to these objectives, with this constraint?

Devising a Strategy

Encouraging more options and supporting continuation assumes support through mentorship, attention, and pathways to funding. Each of these could be given as prizes. Celebrating difference assumes not putting those prizes as a hierarchy.

Non-hierarchical prizes

First and foremost, we decided upon not having a hierarchy to our prizes. We put a cap on the maximum value of awards offered, such that the prizes are more equal. And, unlike last time, we removed cash from the equation. While cash (especially for operating expenses) is a vital part of a project moving forward, it complicates things more than we were set up to handle, especially in immediately setting up a hierarchy of amount given.

Strategic metrics

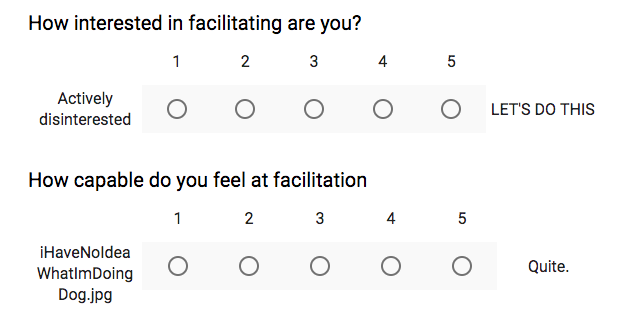

Half of our judges focused on strategic movement towards our objectives, and the other half on pairing with specific prizes. The strategic judges worked with our own Willow as judging facilitator and the MtBNS team to devise a set of priming questions and scales along which to assess a project’s likelihood of furthering our collective goals. You can see where we ended up for overall criteria here.

Awards offered, and who offered them

The other half of the judges were associated with awards. Each award had additional, specific criteria, which are listed on the prizes page here. These judges advocated their pairing with teams where mutual benefit existed.

The process we thought we would do

Day 1

- Post criteria to participants on day 1

- Judges circulate to determine which teams they’d like to cover

- Map the room

- Judges flag the 10ish teams they want to work with

- Teams with many judges hoping to cover them are asked their preferences

- Run a matching algorithm by hand such that each team is covered by 2 award judges and 1 or 2 strategy judges. Each judge has ~5 teams to judge.

Day 2

We hosted a science fair rather than a series of presentations.

- Everyone answered against the strategic questions

- Judges associated with a prize also ranked for mutual benefit

- Discussion about equitable distribution

Award ceremony MC’d by Catherine. Each award announced by a strategy judge, and offered by the judge associated with the award.

Where it broke

The teams immediately flooded throughout the space, some of them merged, others dissipated. We couldn’t find everyone, and there’s no way judges could, either.

There’s no way a single judge could talk to the 40ish teams in the time we had between teams being solid enough to visit and a bit before closing circle. Also, each team being interrupted by 16 judges was untenable. The judges came to our check-in session 2 hours into this time period looking harried and like they hadn’t gotten their homework done on time. We laughed about how unworkable it was and devised a new process for moving forward.

Updates to the process

Asked teams to put a red marker on their table if they don’t want to be interrupted by judges, mentors, etc.

- Transitioned to team selection of awards.

- Made a form for a member of each team to fill out with their team name, locations, and the top three awards they were seeking.

- Judges indicated conflicts of interest and what teams they have visited so we can be sure all teams are covered by sufficient judges.

Leave the judging process during the science fair and deliberation the same.

And — it worked! We’ll announce the winners and reflections on the process later.