My cohort Matt Stempeck at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab recently finished his graduate thesis on participatory aid. We were also on a panel together at the MIT-Knight Civic Media Conference. Here’s a blog he posted on the Civic Blog about his work – it’s reposted here with his permission.

Unlike my thesis readers, who may or may not have made it through all 244 pages, you get to experience the condensed version. The full PDF is here, if you’re into reading and citations.

Participatory Aid

People are using information and communication technologies (like the internet) to help each other in times of crisis (natural or man-made). This trend is the evolution of a concept known as “mutual aid”, introduced by Russian polymath Peter Kropotkin in 1902 in his argument that our natural sociable inclinations towards cooperation and mutual support are underserved by capitalism’s exclusive focus on the self-interested individual. My own reaction is to the bureaucracy’s underserving of informal and public-led solutions.

The practice of mutual aid has been greatly accelerated and extended by the internet’s global reach. I introduce the term “participatory aid” to describe the new reality where people all over the planet can participate in providing aid in various forms to their fellow humans. In many of these cases, that aid is mediated at least partially by technology, rather than exclusively by formal aid groups.

Formal aid groups like the UN and Red Cross are facing disintermediation not entirely unlike we’ve seen in the music, travel, and news industries. Members of the public are increasingly turning towards direct sources in crises rather than large, bureaucratic intermediaries. Information is increasingly likely to originate from people on the ground in those places rather than news companies, and there is a rich and growing number of ways to help, as well.

You are more than your bank account

The advent of broadcast media brought with it new responsibilities to empathize with people experiencing disaster all over the world. For most of the 20th century, the public was invited to demonstrate their sympathy via financial donations to formal aid organizations, who would, in turn, help those in need (think telethons). This broadcast model of aid works well for martialing large numbers of donors, IF a crisis is deemed significant enough to broadcast it to the audience. Many crises do not reach this threshold, and therefore do not receive the public or private relief support that often follows broadcast attention.

People are using the internet to help in creative ways in times of crisis. There are pros and cons to this development, to be celebrated and mitigated. Briefly, the pool of people who can help in some way is now orders of magnitude larger than it was previously, and the value of those peoples’ contributions is no longer limited to the financial value of their bank accounts. People have consistently proven capable of creative solutions and able to respond to a wider range of human needs than formal needs assessment methodologies accommodate.

On the flip side, not every way to help online is as effective as providing additional funding to professional crisis responders. There is already a graveyard of hackathon projects that never truly helped anyone (especially those with no connection or feedback loop from anyone in the field). The expansion of the range of crisis responders can lead to fragmentation of resources and duplication of efforts, although anyone managing the thousands of traditional NGOs that descended upon Haiti following the earthquake there will tell you that the same problem exists offline. It is my hope that open data standards and improved coordination between projects can mitigate some of these issues.

How to Help Using Tech

One of the more celebrated methods of recent years is the practice of crisismapping. Following a disaster, crowdsourced mapping platforms like Ushahidi are populated with geocoded data by globally distributed online volunteers like Volunteer Standby Taskforce. The teams collect, translate, verify, analyze, and plot data points to improve the situational awareness (the “what’s going on where”) of formal emergency managers and organizations.

Of course, participatory aid is not limited to producing crisis maps to benefit formal aid organizations, and I argue we shouldn’t limit our understanding of the space to this one early example. Countless professions have shifted to support the digitization of labor, so many of our jobs can (and are) conducted online (pro bono networks like Taproot Foundation and Catchafire are important inspirations to consider). Over time, technology has continued to expand the range of actions an individual can accomplish from anywhere in the world.

A Case Library of New Ways to Help

To support this argument, I collected a case library of nearly one hundred ways members of the public can help communities in crisis (as well as the formal aid organizations working on behalf of these communities). I still need to convert the full case library from Word to HTML, but you can get a sense of it here.

I spent a lot of time thinking about the many ways people can help using technology, and abstracted from these many cases 9 general categories to organize the library. They are to your left.

Framework

From the many examples in the case library, I abstracted a framework to help define and think about participatory aid projects:

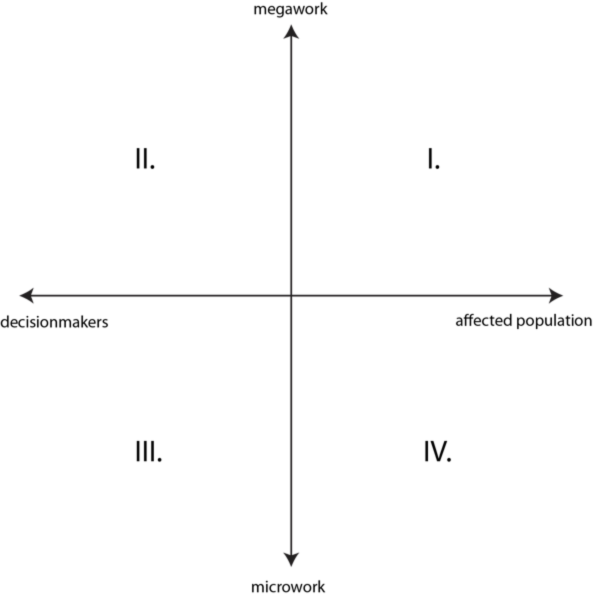

Participatory aid can consist of projects that help existing formal aid groups (like a crisis map created at the request of such an institution) or projects that seek to help the affected population directly (like the Sandy Coworking Map, which listed donations of commercial real estate by and for the people of New York). This is a spectrum, because there are many projects which seek to help the affected population as well as the professionals mediating their aid.

Likewise, there is a spectrum between microwork, which often gets called ‘crowdsourcing’, and far less discrete tasks, like designing an entirely new software project or launching an entirely new public initiative like Occupy Sandy. In my research, I noticed that even some of those in the participatory aid space a limited view of its possibilities, and consider crowdsourced microwork at the behest of existing state actors (quadrant IV) to be the ideal application of technological innovation in crisis response. This is an exciting area, but there’s equally great work being done elsewhere. We can create and execute much deeper, more complicated solutions than helping sort thousands of tweets to extract actionable information. (See Ethan Zuckerman’s discussion of thick vs. thin engagement, which I borrow).

Participatory Aid Marketplace

Because I’m at the Media Lab, I was charged with building a piece of technology in addition to producing the written thesis. After conducting interviews with a wide range of leaders in the participatory aid space (and reading a crazy wide range of documents), it emerged that coordination of efforts was a major and unsolved need. Volunteers are interested in what they can do to help, and prefer to use their professional skills if volunteering (versus making a donation). Leaders of semi-formal volunteer organizations like those that make up the Digital Humanitarians Networkseek common check-in forms to easily alert one another (and the world) to their deployments. The individuals within formal aid organizations (like UN-OCHA) who are working to better integrate participatory aid with formal aid also stand to benefit from improved coordination and aggregation of participatory aid projects.

So, with a team of MIT undergrads (Patrick Marx, Eann Tuann, and Yi-shiuan Tung), I co-designed and built a website to aggregate participatory aid projects. The goals of the site are:

- to index active participatory aid projects by crisis to provide an overview of public response

- to match skilled volunteers with projects seeking their help

- to host the case library of previous examples of peer aid, tagged by the needs they addressed, in the hopes of inspiring future projects

- to do all of this in as user-friendly, open, and distributable ways as possible (including early support for a couple of emerging aid data standards)

A design mockup of the functional Drupal site

The site provides administrators of participatory aid projects with a simple form to list their project. This form populates the active project views as well as the case library, and links projects to common crisis needs and general buckets of volunteer skills. It can also automatically distribute the content to existing coordination fora like Google Groups or RSS readers.

Volunteers can participate in the site with full-fledged profiles, skills<->project matching, and specific LinkedIn skills importing. The more likely use case consists of short, anonymous visits to quickly identify meaningful ways to help in the crises people care about.

The skills selection and importing prototype

Future Work

There’s a lot more in the full thesis, but essentially, we’ve worked with some of the most innovative groups in crisis response to build a functional prototype that would only require some design work and loving iterations to be of real utility. I’m looking into various ways to finish development and implement the site (not to mention identify a good organizational / network home). Get in touch with me if you’d like to talk about the platform, or this space in general.

THANKS

Thanks for reading this.

Also, while I’ve worked for years to use the web to organize people to create change in the world, my background isn’t in humanitarian aid or crisis response. My ability to rapidly understand this space and consume massive amounts of information (written and social) was directly correlated with the kindness and enthusiasm of people like Willow Brugh, Luis Capelo, Natalie Chang, all of my interview subjects, all of the kind survey respondents, and of course my readers, Ethan Zuckerman, Joi Ito, and Patrick Meier. My colleagues, the staff and fellow grad students of the Center for Civic Media, shared their intellectual firepower at every turn.