As y’all probably know, I got married, moved to the suburbs, and had a kid. Because I’m figuring out how to be involved in local politics, I joined the neighborhood association (not an HOA). But I’m still thinking about crisis response. So the natural combination of these things was to get involved in preparedness in my neighborhood. The association has an open meeting twice a year, and I requested that the one last month be focused on disaster preparedness.

We first heard from the city emergency manager. We’re a mid-sized city in the shadow of both SF and Oakland. We have about 100k people who live here, and have 5 public works employees and 80 police. Our fire department is “on lease,” whatever that means (I didn’t want to completely derail the presentation with a deep dive into this) (also, why we prioritize having our own police but not our own fire people is beyond me). The message in this presentation was the same that I’ve heard elsewhere: folks really need to be able to fend for themselves for the first 72 hours. We were told about a risk map (state and neighborhood) and the basics of being prepared (have predetermined emergency contacts; store water, food, and other supplies). The city representative told us about their main issue being how to get the word out – emergency alerts don’t seem to be getting the job done (again, I want to know more about that), so she suggested we sign up for a thing called NIXLE alerts (text your zip to 888-777) that works if the cell towers are up. Radio is still used. We have sirens in my town, but they don’t work.

We also have resilience hubs in my town, and we heard about them from a college intern for the program. These centers keep racial equity in mind when approaching quality of life year-round. The disparity even in the urban tree canopy was called out – more affluent neighborhoods have more trees, which also means they’re cooler in heat waves. Their goal is to help groups “bounce forward” in climate adaptation. Their programming has a few arms – Community Care and Belonging, Disaster Preparedness, Climate Solutions, and Equity – during everyday, disruption, and recovery times. They also strive to have great buildings that can be useful in crisis; plus communications, power systems, and operations abilities (including conflict resolution protocols). I am clearly stoked about all this.

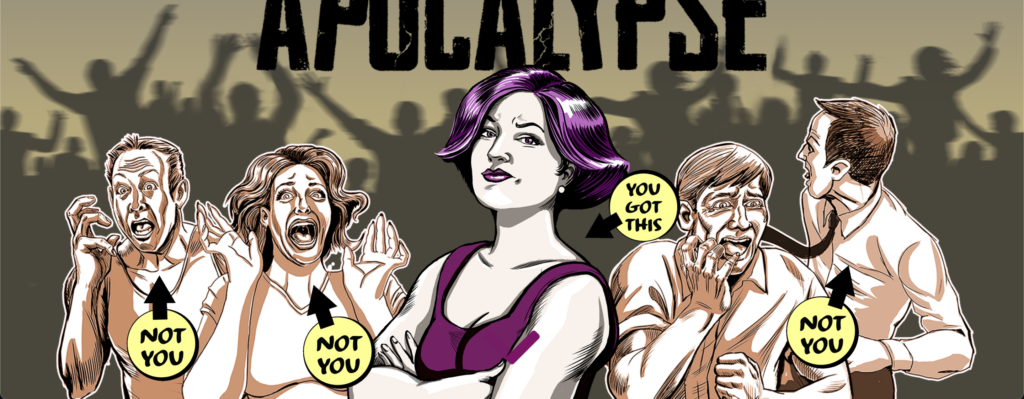

After hearing from the two speakers, I asked attendees to break into smaller groups and talk about what they would like to see happen in our specific neighborhood, and what questions they still had. This was amusing – the attendees hadn’t been asked to be participants beyond taking a mic to speak to a board in the past – but we got some good results! Based on the feedback folks had, I’m going to work with a small group to put together a risk and resource map of our neighborhood for our next Chili Cookoff and BBQ in August, which folks can add themselves to as resources. I’d also like to privately start collecting names and addresses of at-risk neighbors for block captains to check in on during the next heat wave or earthquake or whatever. At the same event, we’ll probably do a prize for the best go bag, and hawk this phenomenal guide another neighbor has put together for preparedness called Here Comes the Apocalypse. I am delighted by this fun visual guide and hope you check it out. I hope Jen and I get to be friends, because she’s brilliant for this.

It’s exciting to merge two things I’m so passionate about – the disaster cycle and my neighborhood. Fingers crossed we never need it, but if we do, we’ll be more ready than we would have been otherwise.