I regularly coordinate a salon over at the New England Complex Systems Institute. For the January salon at NECSI, Ethan and Erhardt led a discussion and workshop on civics in a distributed society. We explored how people with influence/power/money try to create change in the world, how those affected by those changes view and respond to those attempts and changes, and also what we would do as people of influence/power/money.

Many thanks to Ethan and Erhardt for their valuable time and attention as well as images used in this blog entry, and to Erhardt especially for designing such a great workshop, and for suggesting edits to the blog itself. Y’all are pretty great. ❤ – w

Many people want to change the world.

Leverage through money or power

Democracy as it tends to be generally practiced is the act of selecting people for positions of power, and then pressuring them through petitions, protests, and letters. Ethan remarks that this is a remarkably impoverished view. We also interact with governance and our social systems based on what we buy (and don’t buy), where we live, how we speak. However, today our trust is low, and not just in government, but in institutions as well; and not just in the US, but all over the world (see Figure 1). (note: The origins of distrust may be traced to the high complexity of society that makes centralized decision making ineffective.) Many of us would like to change the systems we live in to improve the world. What strategies are available to make such change?

Among those who are trying to make changes are individuals and foundations with large amounts of wealth who strive to act in ways that will improve the world according to their perspectives and understanding. What strategies do they use to exert influence? How successful are they at achieving their objectives? Examples ranging from the Koch brothers to George Soros provide some insight. They might invest in think tanks, in market-based interventions, in campaigns to affect public opinion to place pressure on courts and elected officials.

Regardless of whether an individual came to have influence through an electoral process or through access to wealth, Lawrence Lessig provides a framework in his book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace on which most (if not all) change is attempted.

Four fulcrums

- Laws are explicitly stated codes of behavior, created and enforced through governance systems.

- Norms are often implicit social expectations, enforced through social pressure and assumptions of media and other communications.

- Markets shape behavior by making some actions more or less expensive financially or time.

- Architecture/Code are the frameworks that surround us and must be adhered to because we act within them. Today many of these frameworks are technological which might be called: the tyranny of the database, or how interfaces demand obedience.

How do you know if what you’re doing is working?

The enforcement of laws can be tracked. Market costs can be quantified. The use of an architecture implies success of its constraints (though choices of what architecture to use, and innovators, hackers and other reappropriators, provide freedom). Ethan and Erhardt primarily focus on changing norms. These are also arguably the most difficult to characterize and to discover if a hoped-for-change is occurring, as norms are often implicit, rather than explicit, and are distributed across the statements of individuals, groups and media sources.

At the Center for Civic Media, they think about norms and the attention economy, and one way of seeing shifts in norms in this view is by tracking how the media talks about a topic. They use a tool called Media Cloud for gathering media sources, creating visualizations, and comparing the words used to talk about topics of discourse. For instance, Erhardt analyzed the dynamics of the media conversation around Trayvon Martin through the roles of broadcast and participatory social media.

In short, creating change is hard, even if you’ve got money and/or power.

Here’s the video from our salon:

More on the topic of civics in a distributed society from Ethan’s post about his keynote at Syracuse University’s Humanities annual symposium on Insurrectionist Civics in the Age of Mistrust (highly recommended, and most of the images on this blog comes from the associated slide deck).

How would YOU create change?

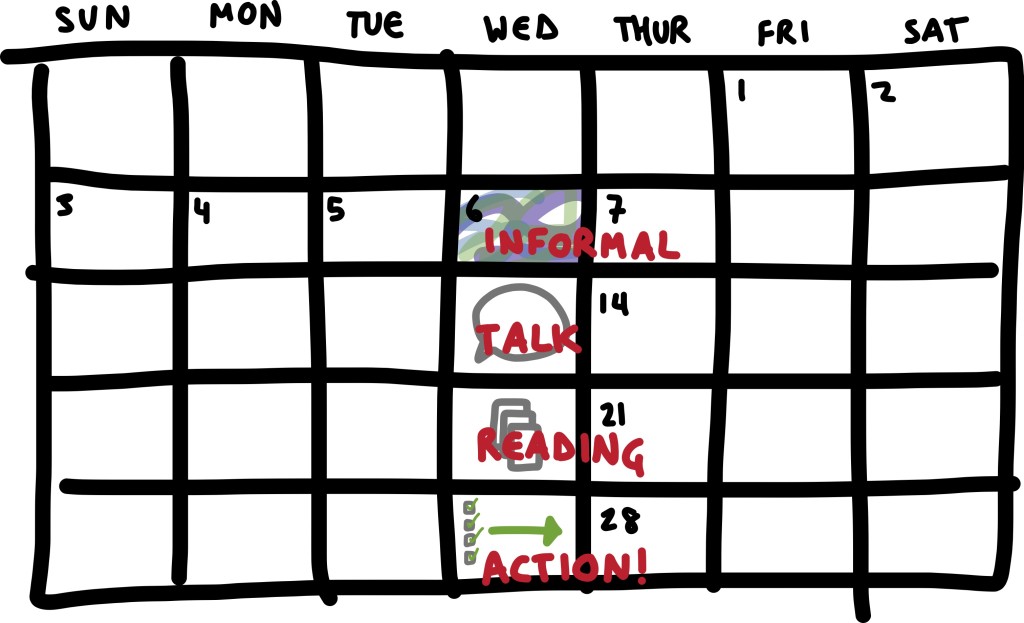

With this framing, this question was posited to the salon attendees. Erhardt facilitated an interactive workshop: “So let’s say you have 10 million dollars. What would you do, about climate change? Fund think tanks and organizations? Fund advocacy groups / passing laws? Fund research? Create tech to do things we can’t otherwise do?” The room divided into 4 groups, and then picked one of Lessig’s four means of interventions and brainstormed ideas.

What would you focus on doing, and how would you know if it was working?

Architecture/Code: Attach sensors to cars, trucks, and environments focused on transportation-based discharges of greenhouse gases. The emissions sensors could provide immediate feedback to drivers and city officials when emissions go to high and trigger sanctions.

Markets: Invest in a startup that offered green logistics/delivery services such as bicycles that would compete with truck-based last-mile services such as UPS and FedEx. Gain market share not just by comparative cost but also by being better for the environment.

Norms: Incorporate data about individuals’ carbon emission from how they live into their online social profiles so that their is an opportunity for social sanctions and desire for self-improvement is publicly viewable.

Law: Create policy that forced power suppliers to develop more resilient grids from renewable energy sources. The data would be monitored by the government for compliance.

We were also joined on Twitter:

@willowbl00 @NECSI I think the Great African Tree Wall is a good start; ban Urban commutes by automobile on penalty of stoning; nuke plants.

— Kevin Foobar (@fu9ar) January 13, 2016

@willowbl00 @NECSI Investments in https://t.co/gNtzicIT9q 2.Battery tech 3.Ending animal agriculture (bigger than transportation) — Ben Rupert (@Meowdip) January 14, 2016

To shift the world, even with massive funding and assumed power, is difficult. All of the interventions discussed at the salon were at a speculative pilot/demo level. To know you’re succeeding through an intervention is also difficult. There was a realization that those who have money and power are often not wildly successful at changing the world because of the difficulty of understanding how constructive change can be achieved. Perhaps a few “why don’t you just…” phrases were put to rest. At the same time, as individual citizens, we saw how much of a role we have to play in societal shifts — perhaps more effectively in our distributed and connected networks.

“The exercise of designing a method for evaluating your campaign’s success often forces you to rethink and get more specific about your original intervention idea. When you need to turn your target and goals into dependent and independent variables to study and then worry about the timeline for change — it really complicates your view of how to make change. And I would say each of the groups felt this.

There was also a clear bias amongst participants toward norms-based change even though they were addressing legal fixes, market forces, or technical architectures. We all want to think that people will know what behavior is the right behavior once they have enough information. The fact that such a process takes many years and many interventions and runs up against cognitive biases where information counter to your position can leave people stronger in their problematic ways, is what makes norms-based change so hard. The goal of making sure that everyone in the workshop had a chance to think about laws, markets, and code as well helps concretize the need for many different approaches: carrots and sticks in various guises needed for a movement to make its mark. And $10mil is not a lot of money to start with.” – Erhardt