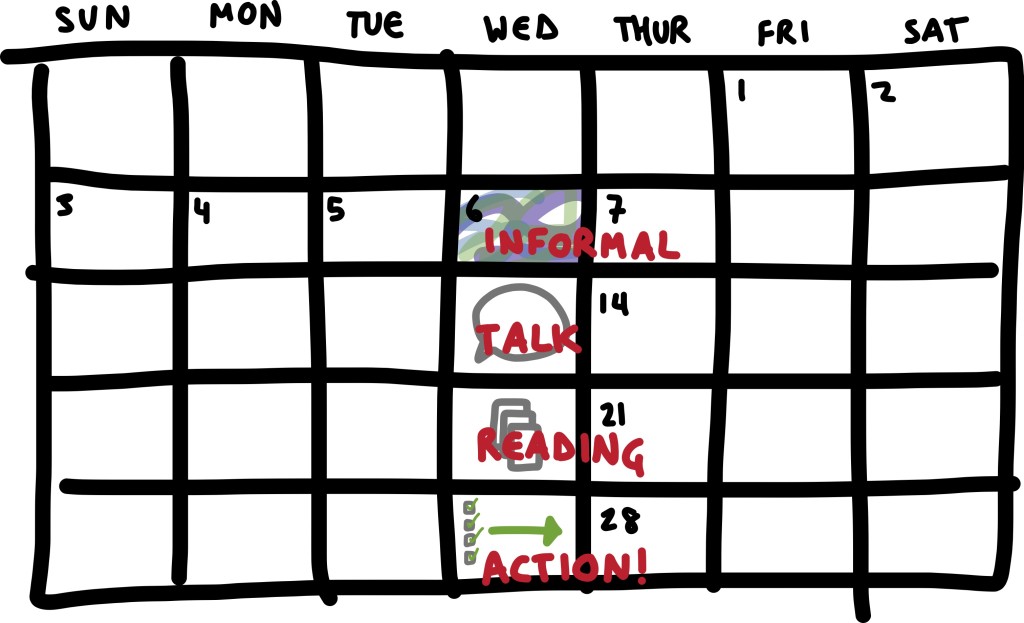

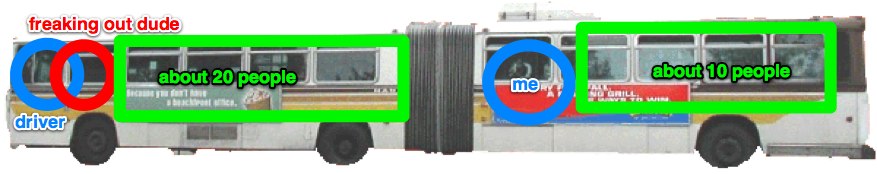

Recently I predictably found myself careening towards the 520 by way of 5, my nose in a book, much like the rest of the passengers aboard. During a moment of looking up from my book – to see the sky, which looks remarkably like this some days (tho not that day), or to prevent car sickness, or whatever – I noticed something odd at the front of the bus. Someone standing by the driver, in that hunched way that usually means aggression but can also mean trouble keeping your balance while standing in a bus that’s moving down a highway at more than 50mph. I looked around. Being towards the back half of an accordion bus means there were plenty of people closer – surely if there was something wrong, one of them would have stepped up. Based on their body language, though, most were actually absorbed in their media. Some of that focus was obviously intentional, rather than on whatever was going on at the front. Not a good sign.

I packed all my stuff away, put my phone and my wallet into my pockets. Asked the person next to me to watch my stuff, and walked towards the front. Walked past maybe 20 people, a few of whom looked up at me while I went by – we’re on an express route, and didn’t have a stop for a ways.

“How’s it going?” I asked, looking at the driver in the mirror.

“It’s.. ok,” he said, making eye contact.

The older, swaying man scoffed, turned to me, and said, “why, what would you do about it?”

“Whatever necessary to return the driver the attention he needs to keep us safe” I responded.

It then became an act of distracting him away from the driver, without having him escalate towards me, while our steersman got us to the next stop safely. The man experiencing angst had missed his stop (a significant thing on an express route), and the driver had not let him off at a non-stop area. Because of safety, and consistency, and because infrastructure does indeed have to adhere to The Rules. But I didn’t ask him about that (he was wrong, and would not have been persuaded otherwise. If he had valid concerns I would have focused on that, and proper channels to deal with complaints), I only kept reminding him that we were ON A BUS ON THE HIGHWAY AND HE WAS DISTRACTING THE DRIVER. I focused on the lives, in a very immediate and pressing way, which were at risk because of this distraction, not his behavior or what had triggered it. Focused only on potential outcome of his current approach. It mostly worked. He tried insults about my hair (heard it), my gender presentation (yawn), his physical superiority (just try). When we had arrived at our stop and he had been booted, I checked in with the driver – does he need my contact in case there is a report? Did he need anything else? – and then returned to my seat. Seething. Why is it an appallingly normal situation that, of all the people in an area, conflict resolution lands on the shoulders of myself and those I keep the company of? I nearly (nearly) had a “sheeple!” moment. And then I took a deep breath and drew a chart instead.

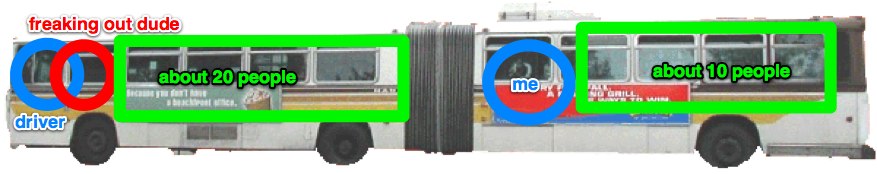

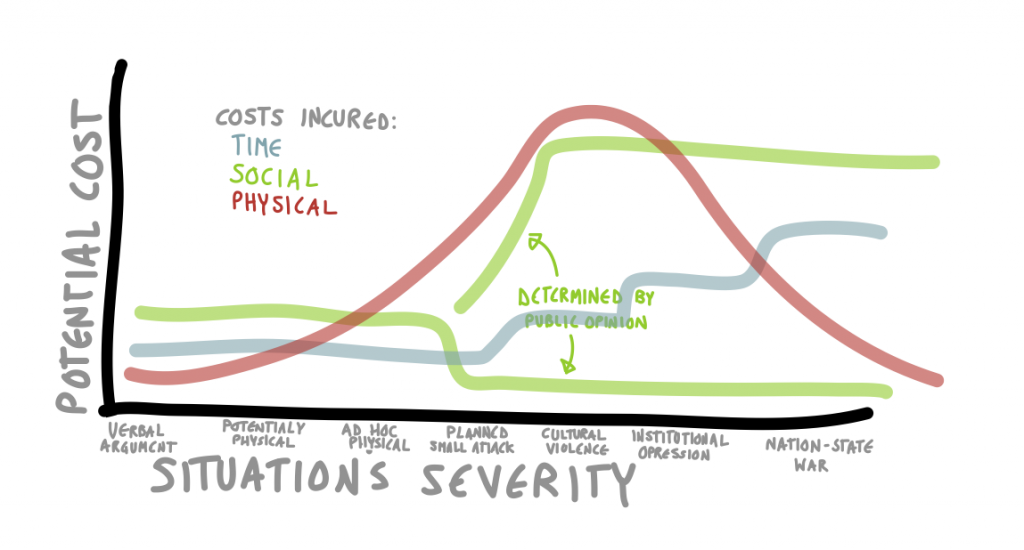

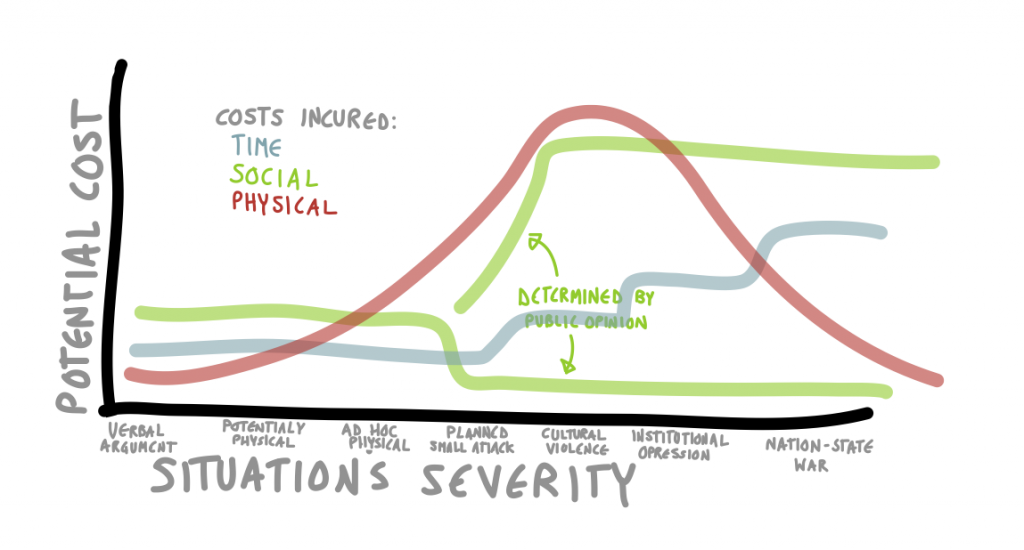

Physical harm based on proximity to incidence. Of course this graph is subjective.

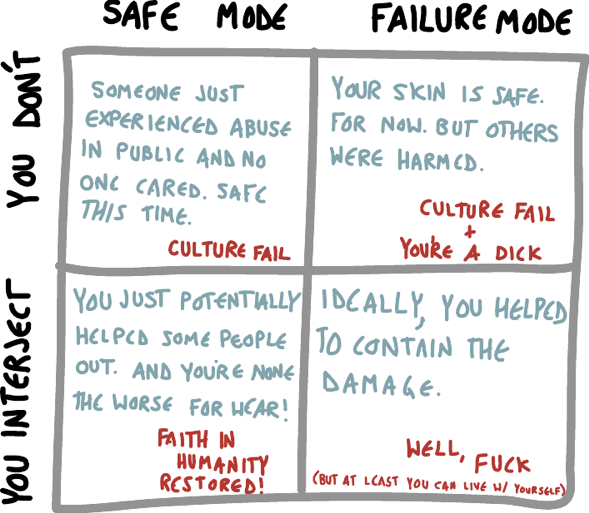

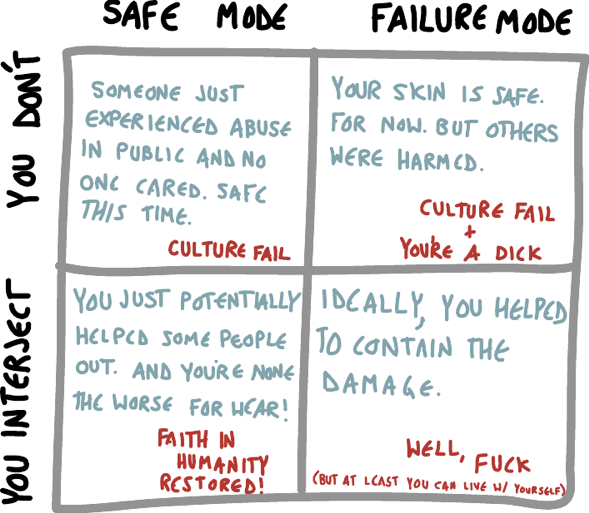

I started to think about why people don’t engage in situations like these. Things like Diffusion of Responsibility have been studied at great length in the past – the same reason asking someone to watch my bag for me is successful is also why individuals don’t step up to help an individual when a large group is present. See the obligatory reference to Bystander Effect and Kitty Genovese (case taken with grain of salt, but Bystander Effect is well established). But I would hope that the people I associate with would actively dislike being a bystander, and are simply lacking the understanding of how to engage.

Here’s a quick run-down on how I engage with conflict. The base assumption being that you HAVE to, as you’ll be the only one. (Except for when you’re not, and the beauty of a group of strangers coming together around a pressing issue is beautiful. You will be supported, and supporting someone else. Just because one person has stepped up doesn’t mean you shouldn’t as well.) First, you have to assess the situation. These are generalities and non-linear.

- Assess what is going on, severity, is this for you or “official” response, etc. Who is most at risk? Are you protecting or breaking things up?

- What is the end goal?

- Where can you help, if you can? If you can’t help, what needs to happen to assist the situation?

- What sort of engagement can you do, and what is the backup plan if it escalates past that?

Now that you know vaguely what you’re dealing with and what your limits are, it’s time to engage. Certainly contextual to danger you’re not prepared to deal with.

- Check in, usually via eye contact. Do this with the person who is least in control. Also do this with the person in the most control to see if they’re of the persuading type. Ask each how they are doing.

- No matter what insults are thrown, or arguments are made, stick to what your goal is. It can be hard to be rational in these situations, and easy to get pulled into the energy. Stick to your mental guns.

- If needed, enlist someone nearby to call authority figures. You need your attention where it is, and hopefully this means you’ve pulled at least one person out of by-stander headspace into up-stander headspace.

- Oftentimes, just being called on being inappropriate it enough to get an individual or group to desist.

Me, personally, I’m pretty ok with getting into a fist fight so long as I am fairly certain there aren’t any weapons around. While getting hit sucks, the mere willingness to put yourself at that risk deescalates most situations. Think of it like poker, and you’re calling a bluff – but you have to be willing to take the hit if you’re wrong. Here is why I think it’s imperative to take responsibility in these situations, broken down in chart format:

This is important to me because, honestly, sometimes I need backup too. I’m reminded of sitting on the BART, headed to the airport, when two guys came and sat in the seats near me. There was the pretty standard come-ons, accompanied by aggressive body language, clearly trying to box me into the seat. I did my usual progression: first good natured “sorry, not interested, and did you know your approach is kind of awkward?” followed by “not even cute. Piss off.” They even pushed it to the point of dead-on eye lock with “Look. Either persuade me you don’t have balls, or I’m going to remove them.” They got off at the next stop, muttering between themselves. While their actions were appalling, what I found so much more awful were that when I had tried to make eye contact with the other people on the car, of whom there were plenty, no one would. And while I can take care of myself, the thought of someone who is less willing to cause lots of damage (even if losing) seeking help and not getting it makes me feel utterly disgusted.

Our system is incredibly flawed in how we hold perpetrators accountable for their actions. I am not disputing that. But equally (or more) dangerous is a lack of taking bystanders to task. And to that end, I want you to listen to the most recent Brainmeats! podcast on Social Scripts for Abuse, and think about how we can fix this. What role does a community play around bad actors? That community can be social or geographic. As always, it starts with you. Stand up. I hope this has given the beginning structures on which to engage.

Safe space (online and off) isn’t just about policies and retributions, it’s about how we as individuals encourage, expect, and enforce it. It’s not about ego (either it getting bruised if you fail, or bolstered if you don’t), it’s about being able to exist.