Originally posted on the Aspiration blog

For a long time, it wasn’t possible to include everyone’s voice in planning or decision-making without impossibly large amounts of time. There was no way to listen, at scale. So aggregation and centralization became common, especially in times of urgency, even with the troubles these tend to cause.

But now, with the technologies we have, we can *listen*, in high resolution and in high fidelity. But technology isn’t a silver bullet. We also need the political will and the personal values to make that happen. With Aspiration’s new Digital Humanitarian Response program, we get to support some of the rad people willing and able to make these movements happen. In May, we hosted the Humanitarian Technology Festival at MIT. The Digital Response Wiki provides resources and notes, and here are some top-level highlights from the event:

Disaster and humanitarian issues don’t happen in a vacuum

Groups like Public Lab help lay the groundwork (both socially and technically) for fast-cycle disasters, via their ongoing interaction with communities around environmental justice. This also provides scaffolding for handing off responsibilities after an extreme event. Kathmandu Living Labs, a group committed to mapping the infrastructure of their geography, is an excellent case study in this. When the Nepal earthquake hit, they were able to jump into action quickly due to pre-existing Open Street Map communities, workflows, data infrastructure, and (most importantly) social ties. Kathmandu was then capable of making use of (and maintaining) the updated data after the fact. Simply by being (and being allowed to be) active in affected communities on a day-to-day basis, organizations can support communities in becoming more resilient to disasters.

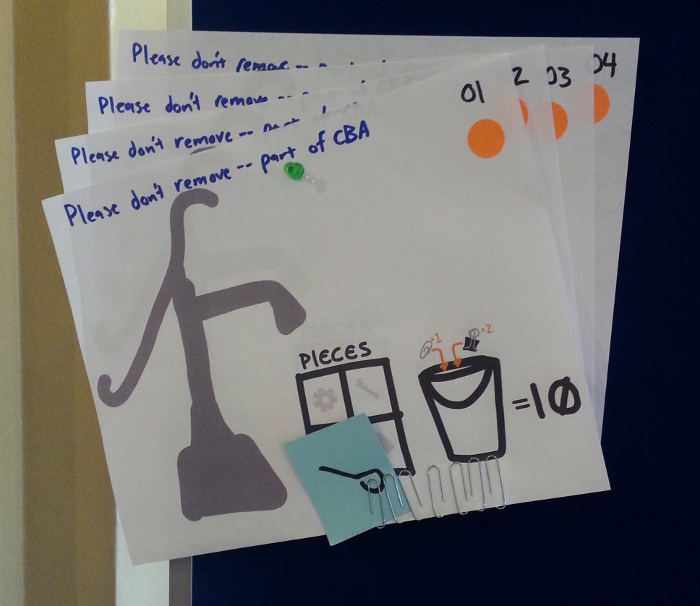

That said, preparing for extreme events before they happen can help mitigate the severity of impact on people lives. We explored the idea of games to make what might be considered dull more fun. No need to start from scratch (though that can be stimulating as well!). Climate Centre makes such games, and publishes them openly over on their website.

We already have much of what we need

One of our spectrogram statements was, “We already have all of the technology we need.” While we were divided in our responses, we acknowledged that the ability of groups of people to make do with what they have in disaster is astounding. And our preferences apply here technically as well as ethically. Distributed, federated systems both for technology and for communities/governance are more resilient than centralized systems (as well as addressing human rights in general). There are a few of these rad systems being built, NYC Prepared being one of my favorites.

Data and consent are deeply linked

Data use with populations that are vulnerable (based on their history, their current circumstances, or both) is still a big question, but not one we need to face on our own. OpenGov, Missing Persons, and other transparency-related initiatives have figured an awful lot of that out, and we should take note. Additionally, while consent is different in high-stress situations than in long-term advocacy campaigns, it should still be a strong consideration in any plan or intervention.

We looked at the Framework for Consent Policies which came out of a Responsible Data Forum in Budapest, and suggested advocating for a “notify this set of people in case of emergency” embedded into social platforms, similar to Networked Mortality or ICE contacts in some phones. This way, people would be consenting and determining who would be their contacting associates in case of disaster (unlike what Facebook recently did). Consent is a component of accountability, both of which highlight how frontline communities might be the architects of their own rescue.

Accountability is just as important in precarious situations as it is in everyday life, if not more so

Accountability is sorely lacking in humanitarian aid and disaster response. Fantastic organizations exist to track where spending is going, but money is often considered misspent. Frameworks exist for deploying aid in ways which alleviate, rather than exacerbate, conflict and tensions. However, these frameworks and mechanisms are still sometimes insufficient, as even well intended groups remain in regions for decades while populations become reliant on them, rather than becoming self sufficient.

Rather than come up with an external group to hold response groups accountable, we figured the frontline community could state whether or not initiatives are working, and those reports could be sent directly to the response organizations, their donors, and relevant constituents. This factors in strongly to the Dialling Up Resilience initiative grant of which Aspiration is a part (Yes, it’s spelled with 2 L’s. They’re Brits). More on that soon.

You can find more thorough notes from Humanitarian Technology Festival on (you guessed it) our wiki. Reach out to us if you have any questions about this ongoing work. Contact us here: humtechfest@aspirationtech.org / @willlowbl00