I’ve started writing about response over on the Aspiration blog, but this one still has cursewords in it, and is very much in my own language, so I figured I’d post it here first.

The problems our planet is facing are becoming more extreme. People and politics mean there are larger populations more densely packed in cities. Nomadic populations traveling along their historical routes are now often crossing over arbitrary (have you *seen* some of the country lines people in Western countries have drawn in places they might never have even been!?) political boundaries, making them refugees or illegal immigrants. Climate change means more and more extreme events are impacting those populations. We have *got* to get our shit together.

In all this, the people who have been historically marginalized often become even more so as those in power see scarcity encroaching on their livelihoods. But the ability to hold people accountable in new ways (through things like social media), as well as (I hope) a real awareness and effort in the long arc towards equality, means there are groups of people seeking new ways to better allocate resources to those most affected by these events. Often, these groups are also in a post-scarcity mentality — that, when we work together, wisely, we can do a whole lot more with a whole lot less. These are folk who think we *can* reach zero poverty and zero emissions (within a generation). These are the folk who see joy in the world, and possibility.

The resource allocation and accountability necessary for these transitory steps towards a world that can survive and even thrive won’t happen in a vacuum. In the organizations, governments, and grassroots efforts there are entire supply chains, and ways of listening (and to whom), and self-reflexive mechanisms to consider. In these are embedded corruption, and paternalism, and colonialism. In these, too, are embedded individuals who have been Fighting The Good Fight for decades. Who have added useful checks and amplifiers and questions. It’s into this environment we step. It is, at its core, like any other environment. It has History.

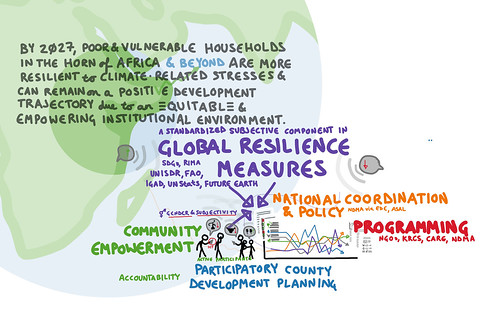

It’s in this context that I’m so excited about Dialling Up Resilience. It taps into questions of efficacy in programming by using and contributing to metrics for success in building resilience. It assumes good faith in policy makers and implementers by offering up data for them to do their jobs better. It protects against bad actors by providing granular, speedy data aggregated enough to protect data providers but transparent enough to be clear when a program is working (or not, if those we’re assuming good faith in don’t actually deserve that). And, my favorite part — instead of contorting and posturing about what makes people able to bounce back faster after a climate-related shock… we just ask them. Of course, it’s a bit more complicated than that. But the core is there.

We’ll be working with a few different groups in Kenya, including the National Drought Management Authority (and their Ending Drought Emergencies program) and UNDP on their existing surveying initiatives, as well as groups like GeoPoll (SMS), Twaweza (call center), and Kobo (household) on stand-alone surveys about how communities estabilish and track their own resilience. If we get the grant extension, we’ll work more directly with communities using tools like Promise Tracker and Landscape (a digitized version of Dividers & Connectors) to be closer to their own data, and to subsequently be able to have more agency over their own improvement as well as accountability.

What’s also exciting is that our means and our ends match. I was recently in Nairobi for a stakeholder workshop with not only the project partners, but also with the organizations which would eventually make use of the data. We’ve been conducting community workshops to test our basic assumptions and methods against reality, as well as to be sure community voice is at the core of each component we consider. We’ve thrown a lot out… and added some amazing new things in. We’re hoping to break down the gatekeeper dynamic of accessing communities in the Horn of Africa, and we want to be coextensive with existing programs (rather than supplanting them). It’s feminist and it’s development and I’m kind of fucking thrilled.