Originally posted on the Truss blog

Most of us rely on documentation in one way or another. In this blog post, we attempt to make the following points:

- Most documentation should be treated as if it is onboarding someone to an organization, project, process, etc.

- Involving multiple people of different practice areas increases the quality and context of the documentation.

- Documentation can help a growing/large organization stay in sync with itself.

- Truss’s onboarding documentation is great and you should check it out.

Onboarding documentation is the most important documentation

“Documentation” is the media object (text, video, images, etc) which explains how to do something. Docs can take the form of descriptive policy, READMEs, How-Tos, welcoming, etc.

Documentation is nearly always worth having, but if you only have time to get one piece of documentation in place, it should be made on the assumption it’s being used to onboard someone to the project, organization, process, etc to which it relates. A person rarely looks at the whole project, organization, process, etc as a whole as that is overwhelming. They instead look for signposts that provide context and support in understanding the system they’re about to interact with.

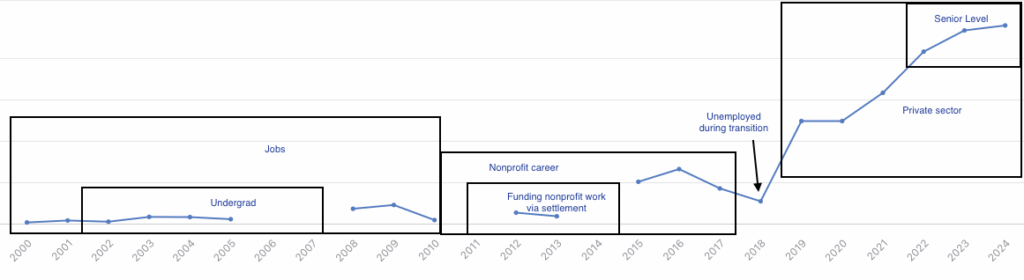

When I got started at Truss long long ago in 2017, we had an onboarding manager checklist but no real guidance for the new Trussel outside of that human contact. Ari, who at the time was doing onboarding (and is now an engineer), is an incredibly high-touch, welcoming human. However, if she or another person helping with the process had a more pressing thing to be doing (which was often the case at a suddenly and rapidly growing consultancy), a new Trussel would stall out and be left in a sea of tasks, new tools, and new people, with a sense of “what even do I do?” And when one doesn’t have a clear path forward, one can feel useless, which is not a good feeling when you’re just getting started somewhere and want to prove your worth.

This was because we had documentation about how things worked, but not from the perspective of the person being onboarded to the organization. If we were to get this in place, a new Trussel would feel more welcomed and solid in their footing.

Luckily(?) I compulsively document things. So as I learned about bits and pieces of the organization, I wrote down in one place what others should also expect as they came in. Oh, we do have a document about PTO? Link it up and give a quick summary. We don’t have one on role definition? Could I help make one? I tried to set it up so when something was unclear or incorrect in the docs, a new person would feel safe enough to ask questions and empowered enough to edit the docs when they learned the answer. This generated a surprisingly long document which was complete enough, but also incredibly overwhelming.

Pouring the firehose into drinkable cups

Documentation takes a bunch of different people of different practices to make it good. Sharing the load also makes creating and maintaining the docs a lighter lift and a shared source of truth and object worth maintaining together.

Our document was way too burdensome, so we called on our design content strategists James and Kaleigh, who suggested it be reformatted into phases of onboarding time. Delivery Manager Amy tried this format out first on her project, and then I expanded it into the MilMove project. When it stuck well enough, we did a card sorting exercise for who wanted to know about which parts of our operations, and when it made sense to learn about them. We also started linking out to external documents when a section got too long or convoluted. This allows people to focus on the big picture, and dive in deeper when something is relevant to them. Then we took our honking document and rearranged it and edited it down to a mere 28 pages.

Just as people had started asking to have new policy or reference docs put into the emerging guide, everyone also helped edit for clarity. It became a thing for more folk to reference and make use of. And just as Nelz, Jeri, Andrew (all engineers), and Mallory (designer) have held my hand in multiple ways to migrate the Guide from a Google Doc to GitHub Pages, many other folk have also refined the Guide to make it what it is. Including our general counsel Burstein writing the best damn disclaimer you ever did see and otherwise making sure we’re not just witty but also reasonable legally.

We have all done this in the spirit of being a warm, welcoming place for new Trussels. All those folk named here (and those I have forgotten 💔) have demonstrated our values in order to make it an easier transition for others to also represent those values.

If you are working on onboarding documents, call in help! Ask tenured folk to verify knowledge is represented, newer folk that it’s clear, content specialists to review structure, etc.

Being able to document something requires understanding it

Growing and large organizations are often accused of “the left hand not knowing what the right is doing.” This has to do with the functions of the different hands not being clear to the other. Enter (you guessed it): onboarding documentation! By describing how different components of a system work, the system itself has opportunities to become more aligned.

One thing that came up time and time again as we worked on the Trussels’ Guide were points of inconsistency or lack of clarity around internal workings. As we grew from 14 to 90 Trussels during the development of the Guide, our processes were also scaling. We became more robust and more formal. But importantly, we always did so with an eye to being comprehensible to an incoming Trussel. Docs shouldn’t only be intelligible in the context of the whole — each should stand on its own in a meaningful way. While most Trussels can’t (and shouldn’t have to) know about every tiny detail of how the business operates, they should be able to look up the details and/or who to ask if they start to care.

As an aside, there’s also this great piece about how you can’t fix a product (or a process) by having good words. The thing you’re describing has to be good, too.

Documenting can surface where things are out of alignment and provide a route to bringing them back into sync with each other. This is important for your organization, project, or process to be functional within the context of itself and the larger systems of which it is part.

A quick how-to

What’s worth documenting? I start documenting when roughly three people ask me the same sort of question. Rather than respond to each separately, I

- try to write it down with the first’s help,

- talk through it with the second, and

- ask the third to try to self-serve with the document created.

This allows emergent areas of interest, guided by our new Trussels, to determine some of the aspects of the business we next define more clearly.

We’re proud of how we do things at Truss and want to share them

So now we are ready, dear reader, to show you how we work at Truss and, as importantly, how we talk about how we work. And so I introduce to you the Trussels’ Guide to Truss. In it are the ways we are kind to each other, how the business functions, some of the decisions we’ve made, and how we embed assumptions into our work.

We hope you’ll have a look, take what works for you, leave what doesn’t, and continue to engage in the conversation of how to build great businesses together. Also, if this seems like the place for you, we’re hiring!