This post was collaboratively written by Liz Barry, Greg Bloom, Willow Brugh, and Tamara Shapiro. It was translated by Mariel García (thank you).

Every year, communities are affected by “extreme environmental events.” These might include hurricanes, earthquakes, tornadoes, or floods. There are, of course, official response agencies with mandates to rescue, feed, heal, and rebuild; however, the true first responders are always people who live in the affected regions — neighbors and community leaders.

The matter of who responds — and who is supported by formal institutional response — is complicated by patterns in which historically marginalized people are often ignored or unseen by outside actors.

These patterns have been further complicated in the aftermath of recent disasters during which spontaneously-forming networks have “shown up” to assist in ways that are more rapid and distributed than is typical of the formal disaster response sector — yet without any of the accountability that formal institutions (supposedly) uphold.

During these experiences, we’ve seen clearly both the promise and the peril of modern digitally-enabled and network-led crisis response and recovery. After 2017’s alarming hurricane season, a network of people formed with interest in improving the capacity for disaster response to more effectively support local priorities and leadership in times of crisis. We are now calling for the convening of people who have worked together through crises such as Sandy, Harvey, Irma, Maria, and the like. At this “Crisis Convening,” we will share experiences and skills, explore ways to promote equity and justice through modern crisis response, and build resources for the type of assistance that we offer.

Here is our key question: in times of climate crisis, how can outsiders — formal ‘disaster response institutions,’ grassroots community organizers from other locations, emergent networks of volunteers on the ground, and ‘digital responders’ — most effectively engage and support community-based responders to achieve a more accountable, humane, and adaptive response?

At this ‘Crisis Convening’ event, we will converse and take small, actionable steps towards addressing some of the following questions, and many more we haven’t considered:

- How can formal institutional responses best support those who are most impacted by a crisis?

- How can spontaneously forming networks provide assistance in a way that centers the needs, interests, and leadership of people who are experiencing the crisis?

- How can we ensure that data about a community stays in that community’s control?

- In what ways are environmental justice and disaster response related?

- How can outside intervention support recovery as well as response?

We hope you’ll join in this conversation with us here, or (better yet!) at the event. If you are interested in participating in the convening, please fill out this form to let us know – and we’ll be in touch.

About the Event

We’re excited to announce that we’ve been invited by Public Lab to host this convening during their upcoming network gathering on July 13-15, in Newark, NJ.

Public Lab is an open community which collaboratively develops accessible, open source, Do-It-Yourself actions for investigating local environmental health and justice issues. Twice a year, they convene in an event called a “Barnraising” in the spirit of coming together to achieve something larger than can be achieved alone. At a Barnraising, people share advocacy strategies through telling stories from their lived experience, build and modify tools for collecting data, deeply explore local concerns presented by partner organizations and community members, and connect with others working on similar environmental issues across regions.

During this convening, we will gather between 30-60 people from areas that have been hit by climate crisis in the past 15 years to discuss real-world scenarios and discuss actionable steps to help ourselves and others practice more effective community-centric crisis response.

Here’s how we hope to do that:

Dedication to local voices and representation

The impacts of crisis often fall heaviest on those who are already struggling. We hope to include those most impacted, though we also understand such folk might have a diminished capacity to engage. To address this, we are inviting an intentionally broad set of people, actively supporting child care at the event, and offering scholarships to those who express interest and need.

We will need all kinds of help to make this happen. Will you sponsor a participant who wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford to participate? Click here to contribute to travel and accommodation costs.

An advance day for Crisis Convening

On Friday, July 13th we will gather to focus on the matter of crisis response. Attendees are encouraged to have a quick conversation with the facilitator in advance to shape the agenda. We might share skills, contribute to a resource repository for communities entering a time of crisis, or further explore how inequality plays out (and can be counteracted) in response.

Public Lab Barnraising

Building on the energy coming out of the Crisis Convening, we can continue our conversation in the same location Saturday and Sunday as more people join for Public Lab’s Barnraising. On the first morning of the barnraising, all participants, including those from Crisis Convening, will collaborate to create the schedule via an “Open Space” approach. This process will ensure that the agenda speaks directly to the interests of the people present. Crisis Convening delegates will be welcomed to add their topics to the schedule. The Code of Conduct applies here as in all other Public Lab spaces.

Please Let us Know What You Think

- In comments

- Reach out to discuss directly

- Join us at the event. If you are interested, please fill out this form to let us know. We will follow up with an official registration form shortly

- Sponsor a participant who wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford to participate. Click here to contribute to travel and accommodation costs

Together, we hope to discover small, actionable projects together which will equip community-first response, whether through organizing, technology, institutions, or things we have yet to discover. We hope you will join us.

Este post fue escrito en colaboración por Liz Barry, Greg Bloom, Willow Brugh y Tamara Shapiro. Fue traducido por Mariel García.

Cada año, hay comunidades que son afectadas por “eventos ambientales extremos”. Éstos pueden incluir huracanes, terremotos, tornados o inundaciones. Por supuesto, hay agencias de respuesta oficial con mandatos para rescatar, alimentar, reconstruir, etcétera; sin embargo, los verdaderos primeros intervinientes siempre son personas que viven en las áreas afectadas: vecinos, líderes comunitarios, etcétera.

La cuestión de quién responde, y quién recibe apoyo por parte de la respuesta institucional formal, es complicada por los patrones en los que poblaciones históricamente marginadas tienden a ser ignoradas o no vistas por actores externos.

Estos patrones se han complicado aun más en las secuelas de desastres recientes a lo largo de las cuales redes de formación espontánea han “llegado” a asistir de maneras que son más rápidas y distribuidas de lo típico en el sector de respuesta formal a desastres, aunque sin la rendición de cuentas a la que las instituciones formales (supuestamente) están sujetas.

A lo largo de estas experiencias, hemos visto con claridad la promesa y el peligro de la respuesta a y recuperación de crisis modernas, habilitadas por tecnologías digitales y redes. Después de la alarmante temporada de huracanes en 2017, se formó una red de personas con interés de mejorar la capacidad de respuesta en desastres para apoyar liderazgo y prioridades locales de manera más efectiva en tiempos de crisis. Ahora estamos llamando a personas que hayan trabajado juntas en crisis como Sandy, Harvey, Irma, María, y otras similares. En esta “Reunión de crisis” compartiremos experiencias y habilidades, exploraremos maneras de promover equidad y justicia a través de la respuesta moderna, y construremos recursos para el tipo de asistencia que ofrecemos.

Aquí está nuestra pregunta clave: En tiempos de crisis climática, ¿cómo pueden los extranjeros (las instituciones formales de respuesta a desastres, líderes de desarrollo comunitarios de otros contextos, las redes emergentes de voluntarios y las personas que hacen respuesta digital) involucrarse y apoyar a los respondientes locales de la manera más efectiva para promover la respuesta más humana, adaptativa y responsable?

En esta “Reunión de crisis”, conversaremos y tomaremos pasos pequeños y accionables para abordar algunas de las siguientes preguntas, y otras más que aún no hemos considerado:

- ¿Cómo pueden las instituciones de respuesta formales apoyar de la mejor manera a aquéllos que son impactados por una crisis?

- ¿Cómo pueden las redes de formación espontánea proveer asistencia de una manera que se centre en las necesidades, intereses y liderazgo de quienes están experimentando la crisis?

- ¿Cómo podemos asegurarnos de que los datos de una comunidad queden bajo el control de esa comunidad?

- ¿De qué maneras están relacionadas la justicia ambiental y la respuesta a desastres?

- ¿Cómo puede la intervención externa apoyar tanto la recuperación como la respuesta?

Esperamos que te unas a esta conversación con nosotros aquí, o (mejor aun) en el evento. Si estás interesado/a en participar en la reunión, por favor llena esta forma para comunicarlo, y nosotros nos pondremos en contacto contigo.

Acerca del evento

Nos emociona anunciar que nos invitó Public Lab a ser anfitriones de esta reunión en la próxima reunión de su red del 13 al 15 de julio en Newark, NJ.

Public Lab es una comunidad abierta que colabora para desarrollar acciones accesibles, de código abierto en el espíritu de “Hágalo usted mismo” para investigar salud ambiental local y temas de justicia. Dos veces al año, se reúnen en un evento llamado “publiclab.org/barnraisingBarnraising” (“construcción del rebaño” en inglés) en el espíritu de juntarse a lograr algo más grande de lo que se puede lograr en soledad. En un barnraising, la gente comparte estrategias de defensa a través de contar historias de su experiencia vivida; la construcción y modificación de herramientas para recolectar datos; la exploración de preocupaciones locales presentadas por contrapartes organizacionales y miembros de la comunidad; y la conexión con otras y otros trabajando en problemas ambientales similares en distintas regiones.

Durante esta reunión, juntaremos entre 30 y 60 personas de áreas que han sido afectadas por crisis climáticas en los últimos 15 años para discutir escenarios del mundo real y pasos accionables para ayudarnos a nosotros y a otros a practicar respuesta de crisis centrada en la comunidad de manera más efectiva.

Esperamos hacerlo de la siguiente manera:

Dedicación a voces locales y representación

Los impactos de la crisis seguido caen con mayor peso sobre aquéllos que están de por sí batallando antes del evento. Esperamos incluir a los más afectados, aunque también comprendemos que estas personas podrían tener una capacidad disminuida para involucrarse. Para abordar esto, estamos invitando a un conjunto intencionalmente amplio de personas, activamente apoyando el cuidado infantil en el evento, y ofreciendo becas a quienes expresen su interés y necesidad.

Necesitaremos todos los tipos de ayuda para lograr este cometido. ¿Podrías patrocinar a un participante que de otra manera no podría costear su participación? Haz clic aquí para contribuir a los costos de viaje y estancia.

Un día de preparación para la Reunión de crisis

El viernes 13 de julio nos reuniremos para enfocarnos en el tema de respuesta de crisis. Se alienta a las y los participantes a que tengan una conversación rápida con el equipo de faclitación con antelación para influir en la agenda. Podemos compartir habilidades, contribuir a un repositorio de recursos para comunidades que entran a un tiempo de crisis, o explorar más cómo las inequidades operan (y pueden ser contrarrestadas) en la respuesta.

“Barnraising” de Public Lab

Para aprovechar la energía resultante de la Reunión de crisis, podemos continuar la conversación en el mismo espacio el sábado y el domingo con las personas que lleguen al Branraising de Public Lab. En la primera mañana del barnraising, todas las personas que participen, incluyendo a las de la Reunión de crisis, colaborarán para crear la agenda a través de la técnica de “espacio abierto”. Este proceso ayudará a que la agenda apele directamente a los intereses de las personas presentes. Las y los participantes de la Reunión de crisis serán bienvenidos a añadir sus temas a la agenda. El Código de conducta aplicará en éste y todos los demás espacios de Public Lab.

Por favor dinos qué piensas

- En los comentarios

- Contactándonos para platicar directamente

- Viniendo al evento. Si te interesa, por favor llena este formulario para informarnos. Te contestaremos con una forma de registro oficial.

- Patrocina a alguien que de otra manera no podría costear su participación. Haz clic aquí para contribuir a los gastos de transporte y estancia.

Juntas y juntos, esperamos descubrir proyectos pequeños y accionables que equipen respuesta donde la comunidad esté adelante, ya sea a través de la organización, la tecnología, las instituciones, o mecanismos que tenemos aún por descubrir. Esperamos te unas a nosotros.

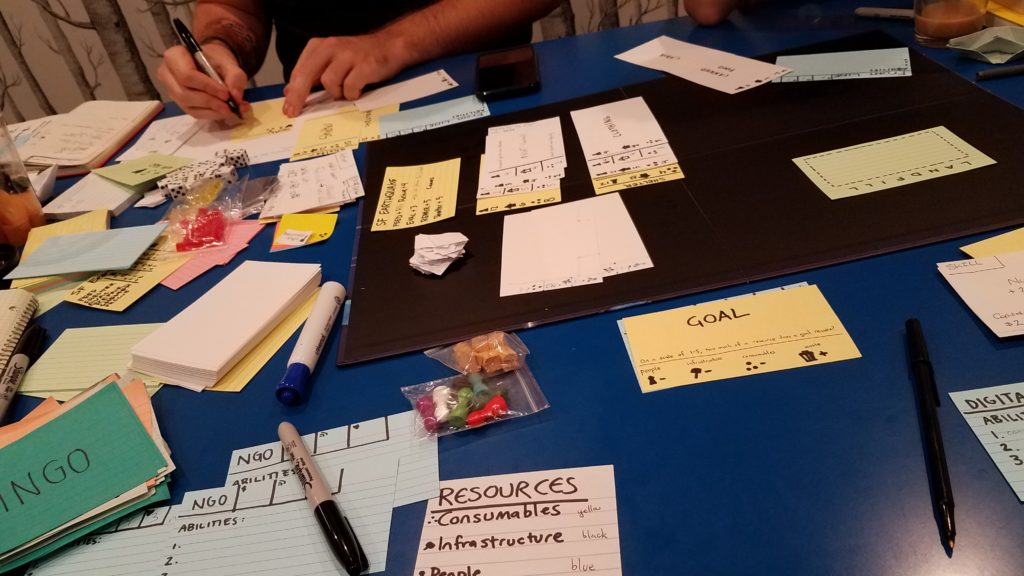

We’ve since continued cleaning up the documentation and refining the game process. And so dear readers, I’m excited to tell you about how this game works, how you can play, and how you can (please) help improve it even more.

We’ve since continued cleaning up the documentation and refining the game process. And so dear readers, I’m excited to tell you about how this game works, how you can play, and how you can (please) help improve it even more.