Been working the new job with Aspiration in SF (while I still live in Providence and Cambridge), which is outstanding. Also been working on a paper about the topic I’m focused on with Aspiration, of how we perform mutual aid, at scale, specifically in disaster response and humanitarian aid. It calls for what we’d call a “mixed-mode system” in Complexity Science. I gave a talk at Berkman Center yesterday on the topic, and they’ve already got the video live. I had a great time! Thanks to everyone for coming out and sharing your brains with me.

Category Archives: Humanitarian Efforts

NECSI Salon: Ethnic Violence

On January 28th, the monthly salon gathered at NECSI to discuss ethnic violence from the lens of complex science. Yaneer Bar-Yam, president of NECSI, gave a brief talk about NECSI’s paper about modeling violence. Marshall Wallace, past director of the Listening Project, also gave a quick talk about his field experience with communities who opt out of violence. Again on Feb 4th, NECSI hosted an informal discussion around the case study of Libya. What follows are my big take aways and Sam’s asides, embedded into the fairly rough live notes from the salon. I call out these take aways and asides specifically because note takers often are lost in the notes, just as a photographer is never in the picture.

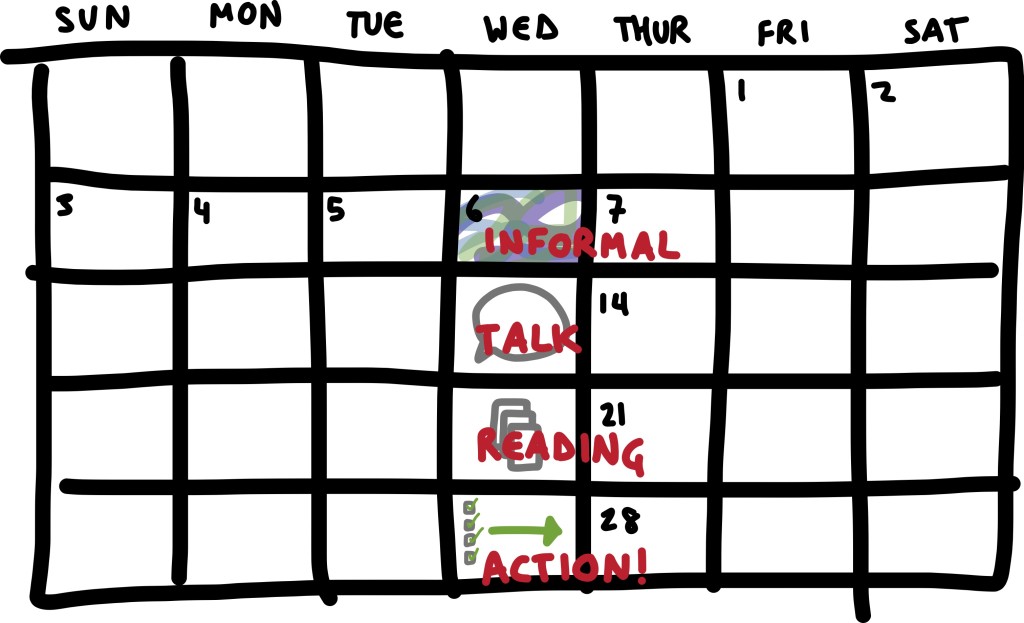

We hope you’ll join us on Wednesdays of this month to begin exploring medical systems, on ensuing fourth Wednesdays for structured discussion, or on other Wednesdays for more informal times.

Register for this fourth Wednesday here.

I am primarily left with a sense of purpose towards fostering collective intent towards alleviating suffering. In this entry, you’ll see a few ways large-scale violence is posited to be avoided. It is my personal opinion (of which I will opine at the end) that diversity is the key to equality as well as dignity, based on both the complex systems modeling and field experience framing these discussions.

But first, what do we even mean by “violence”? We’re referring to violent events occurring at level of massacres or bombing. These levels do seem to be slightly contextual based upon general violence levels in the area. Continue reading

Complexity Salon : Ebola

These notes were taken at the 2014.Dec.18 New England Complex Systems Institute Salon focused on Ebola. Sam, Willow, Yaneer contributed to this write-up, and 20 people were in attendance. We hope you’ll join us in future. We’ll have unstructured meetings each Wednesday from 18:00 to 20:00 (6p-8p) starting Jan 21st, with the fourth Wednesday of each month structured towards contribution towards a global challenge. The next such structured event will be on January 28th, on the subject of ethnic violence. You can see notes on this and potential future subjects here, and can register here.

About Ebola at NECSI [briefing by Yaneer]

NECSI has a history of studying Ebola models, and has predicted something similar to what is currently going on in West Africa for some time now. NECSI started with a model of pathogen evolution in which the most aggressive stable state has virus constantly passing slowly through populations, creating islands, dying out as people expand into areas with no disease.

Aggressive diseases plus long-range transport

Then if you add long-range transport, you get more and more aggressive strains. The more long-range transport you have the more aggressive the strain can be without dying out; and eventually could kill an entire global population. Paper published in 2006, mentions risk of Ebola.

As transportation becomes more pervasive, vulnerability increases.

Early warning and preparedness

Presented to the WHO in Jan ‘14. They were respectful and excited by the work. Discussed other public health issues faced by WHO, however didn’t return to pandemic models.

Since then: outbreak happened. Lots of discussion. Why don’t we engage in risks in a more serious way? Everyone thinks their prior experience indicates what will happen in the future.

- Look at past Ebola! It died down before going far, surely it won’t be bad in the future.

- Models of outbreaks look at existing conditions, which prove to be too limited here.

Example: with flu, people take exactly that disease and known circumstances, and simulate an outbreak, ignoring changes in the disease or in the conditions (and: nothing has to change in order to have huge risk). the same properties could remain, but a low-probability event could unfold, “fat tail distribution” – past experience isn’t necessarily a predictor of what will happen in the future.

Individual and community

Contract tracing, the standard public health method, doesn’t work well when there are more than just a few cases. Stop thinking about the contacts of the person, think about the community. Travel restrictions so new communities aren’t infected. Now that people go door to door for symptom screening, the cases have decreased dramatically in Liberia.

People were saying: “The beds are empty!” Authorities responded: “We can’t figure out why. We think people are still sick!” Why are the hospitals and authorities waiting for the sick to show up? Going door-to-door in the neighborhoods shows what’s going on, and is what is effective.

Once you know the right question, the answer is clear.

Interests

We then stated our interests – each person said one thing about the topic or intro talk they’d be interested in diving into more during breakout groups Continue reading

Museo aero solar

Years ago, after Chaos Congress, Rubin insisted we go to some art show. I, as always, preferred to stay at home — whatever continent, country, city home might be in that day. But Rubin can be lovingly persistent. It would be worth it. It would be beautiful. We went, mere hours before I boarded a plane from somewhere to somewhere else.

Biosphere was a study in liminality to me, suspended spaces tethered to more commonly understood as habitable floors and walls. Perfectly clear water in heavy plastic and vast space define in clarity and iridescence. It was a liminal future, an in-between home, the moment the wheels leave the runway. The terror of my anxiety and the complete love for the possibility of Something Different, wrapped up in the moments of stepping into the future. In short, Rubin was right.

Jump forward a few years.

When Pablo invited me to Development and Climate Days in Lima, I was glad to go. Even before the deeply pleasurable and productive Nairobi gig with Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre and Kenya Red Cross, I trusted Pablo to have spot-on inklings of the future. Maybe all that climate forecasting has gotten into his social forecasting as well. His efforts around serious games resulting in their now being generally accepted, he told about an art-involved step to get people to think about the future differently. Something about plastic bags, and lighter than air balloons. Would I be willing to, in addition to my talk, document their process of creating a Museo Aero Solar for others to participate and replicate? Of course – distribution of knowledge, especially with illustration and technology is kind of my jam. It would also help me venture into the city.

I arrived at 2a to a deserted city and a vast and rolling Pacific out the cab window. I cracked jokes with the driver based on my poor grasp of Spanish (“ehhhh, Pacifico es no muy grande.”) He humored me. And in the morning, mango that tasted like sunlight, and instant coffee, and the Climate Centre team of whom I am becoming increasingly fond. And a new person – the artist Tomas, with whom Pablo and I ventured to an art space to join the already-started process of community building and art creation, large bags full of plastic shopping bags ready for cutting and taping. Pablo eventually had to go spend time at COP20, I relished not going.

I took such specific, ritualistic care with each plastic bag. Cut off the bottom, cut off the handles, cut a side to make a long rectangle. Lay it gently on top of the pile, pressing down to smooth and order. Pick up the next bag. Feel it on my hands. The crinkle, the color. Smooth it out. Cut. Place. The sound of tape being pulled, torn, applied, and stories told in Spanish. The slow joining of each hand-cut rectangle. I smiled, to dedicate so much care to so many iterations of things which are the detritus of life. Francis laughed with me, saying she felt the weight of each one. A heavy statement for something so light. Tomas walking around, constantly seeming to have attracted a bit of plastic bag handle to his heel, no matter how many he peeled off, a persistent duckling of artist statement.

We went to the Lima FabLab to speak to a hackathon about making a GPS and transponder so we could let the creation fly free without endangering air traffic. And this time I saw it from the outside – seeing Tomas speak to a group of self- and community-taught Peruvian coders, and seeing their faces display disbelief and verge protection against the temporal drain of those outside your reality. Then, as he showed step by step, and finally an image, that these can fly, their cousins can lift a person, grins break out. Peoples’ hearts lift, new disbelief replaces the jaded. There is laughter and a movement to logistical details.

And then we took it to the D&C venue, and it worked.

D&C Days #zerozero participants inside solar-powered, lighter-than-air sculpture. pic.twitter.com/DuwaezGxWs

— Climate Centre (@RCClimate) December 6, 2014

I imagine what Pablo must have gone through, to get bureaucratic sign-off on this. No metric of success. No Theory of Change. Him, fighting tooth and nail for a large and hugely risk-adverse organization to trust fall into the arms of a community, an artist, a facilitator, and a game maker. And they did. And it changed the entire event. People in suits crawling into this cathedral made of plastic bags, each individually cut and added with love to the whole. A pile of fancy shoes outside the entrance, like a ballroom bouncy castle. People’s unabashed joy watching art some of them had made become a room, and then lift off to become a transport.

This future we want — it’s hard work, it can seem impossible. But it’s right here, we made it. It works, and it is beautiful.

I brought up ways for other people to participate. In a beautiful act I would associate with Libre ethics, the Lima crew have opened up not only our stories, but our process. We want you to join us. We want you to be a part of this future, and it means hard work. The fledgling wiki and mailing list can be found here. I hope you hop on.

Heatwave Hackathon

Hugs and thanks to Lindsay Oliver and the Kenya Red Cross team for their contributions to this entry.

On November 15th, I helped facilitate the Red Cross Crescent Climate Center’s HeatHack 2014, a gathering of amazing people to collaborate on solutions to climate-related challenges. This event focused on the risks and impacts of heatwaves, and how to provide community care and safety nets for at-risk people during extreme weather episodes.

In case you wonder what a hackathon is:

A hackathon is a gathering of diverse people who form teams to work on addressing challenges over a short period of time. These challenges can be technical, physical, resource-based, or even social. During HeatHack, participants learned about heatwave challenges from climate experts and people who have experienced heatwaves firsthand. Teams formed around potential ways to address these challenges, and worked together to come up with solutions to present to the judges. Prizes were awarded based on innovation, documentation, usability, and inclusiveness.

Why “HeatHack”?

Heatwaves can cause power outages, wildfires during a drought, buckling and melting roads, burst water lines, and serious health effects such as severe sunburn, heat cramps, heat exhaustion, heat stroke, and death.

- According to NASA, when the temperature hits 95*F (35*C) your ability to function drops by 45%. Your loss of accuracy is 700%.

- MPR News reports that body temperature can rise to 105*F (40.6*C) if working outside in a heatwave. Death occurs usually when a body temperature reaches 107.6*F (42*C).

Despite the severity of heatwaves, the health risks often go unnoticed because the people most affected are easily overlooked in a large population, especially if they are poor. We need to create ways of responding to these challenges to care for people who are currently at risk and to prepare for future heatwaves. As the effects of climate change become more severe, the number, length, and temperature of heatwaves will increase – including in Nairobi! Climate change affects the entire globe, and Kenya can lead the way in creating solutions that help as many people worldwide as possible. Continue reading

A month in Nairobi

Background of the gig

Pablo and games

I met this guy named Pablo Suarez in a pub in Boston, when our mutual friend John Crowley insisted I leave my introvert-hole. When John insists, I tend to listen. And as always, it was totally worth it. Pablo plays games. As a climate scientist, he got tired of people falling asleep in meetings. He was aware of the direness of the situation, but no one else felt the same urgency. So he started expressing probability and costs and delays through dice, and beans, and objectives. He’s played these games with people who live in disaster-prone areas on through people at the UN who make policy about resource allocation. He’s created actual, connected change through an entire system. We’ve since embarked upon a few event adventures together, and I’m glad to call him friend and cohort.

My experience with KRCS

And so I met this guy named Dr James Kisia, when Pablo suggested I take a gig at the Kenyan Red Cross. In a continuing trend, when Pablo suggests things, I tend to listen. James has become well known as an innovator in the NGO/innovation space. As an example, reframing the understanding and practice of social entrepreneurship in resource-poor settings. Exploring sustainable resource mobilization for an organization whose relevance in disaster-prone Kenya is increasingly becoming apparent. The KRCS runs 3 hotels in Kenya, taking advantage of the fact that conferencing is a major business in Kenya, and in Nairobi particularly. It might seem paradoxical, having a five star facility on the campus of the a humanitarian organization, but the money the hotels make is ploughed back into the humanitarian work of the organization — including non-funded sudden onset disasters.

Based entirely on good faith, shoe strings, and a few well-placed calls, James and I embarked upon a trust fall with each other, based entirely on Pablo’s word. The Web of Trust in real life. I arrived to Nairobi for 4 weeks of work with little guidance beyond to lay groundwork for a Dadaab-focused intern or contractor, as specific to what would be applicable to climate change issues as well. Continue reading

Another Whirlwind Tour

The Bank booked my tickets for me (yay no financial overhead!.. but–) with an 11-hour layover at LHR. So I popped on the Heathrow Express to Paddington. I’m sitting in a Starbucks, of all places. They’re playing Morrisey. It’s pretty awful, but it’s also a holiday and everything else around here was closed. I was meant to have been back in Boston for the past week, after a long stint of travel, but things got extended by a continent, so here I am.

Cascadia.JS

I gave a keynote at Cascadia.JS, and the event and its people were absolutely wonderful. Even played some pinball with Case (oh, PS, we’re throwing a CyborgCamp at MIT in October and you should come). I was soooo stressed when I gave this talk. Not from the talk itself – this community is lovely! I even wrote about it on the Civic blog – but because of the things surrounding this entry. When I watched the video later, it’s actually pretty alright. They gave me a full 30 minutes, and I wish I had padded it with more information. C’est la vie. Huge huge hugs to Ben and Tracy and the rest of the crew. You made a rough time easier through your care.

The drawings I did for other people’s talks are all here.

Wikimania

This was my first Wikimania, and it was stunning. So so much fun. Many things to think about, frustrations in new light, conversations over cider, and even more stick figures. And! Some lovely person taught me how to upload my drawings to the commons, and so now I’ll be hosting from there instead of from Flickr. Got to spend too-short time with Laurie (who I’ll see more of in Boston! Yay!), AND found out about Yaneer’s work on networked individuals and complex systems which rings closer to true in my intuition than most anything else I’ve run across recently.

Getting to know a neighborhood in London that I actually like, with art in the alleys and a bike repair and tailoring shop with a pub and wifi while you wait that is totally hipster gentrification and I so don’t care. And a strange moment in a Bombay-style restaurant of a half-recognized face, that ends up being the brother of the heart-based Seattle ex-Partner. We hug fiercely (as is the way of his family, and mine), until his manager gets angry. We laugh and promise to catch up.

Thence to Future Perfect, through the too-early fog of morning, and a panic attack, and dear Sam handling the accompanying compulsive need to stick to The Plan, even if it did not make the most sense, with the sort of calm curiosity and fondness which is exactly what is needed in those moments, and jogging through far away airports to finally arrive at our not-even-yet-boarding gate.

Future Perfect

A short flight (slept through) and a longer ferry ride (also slept through) through the archipeligos of Sweden, and Sam and I are on the island of Grinda for Future Perfect. We’re here at the behest of one Dougald Hine, long-time mirror-world not-quite-yet-cohort, to be Temporary Faculty at the festival, and to “difficultate.” It’s a strange thing, to be encouraged to ask the hard questions, and Ella and I are a bit adrift in the new legitimacy of our usual subversive action. “Ella, I think we’ve just been made legible.” “Shit. Quick, act polite!” But there’s an awfully strong thread of Libertarianism and Profiteering From The Future, so it’s not a difficult thing to ask stir-up questions. I sit on a panel called When Women Run the World, and mock the title, and question the assumption of binary sex, and point out matrixes of power. I draw as people talk, and post the print-outs to a large board for all to see, a strange combination of digital and analogue. Another panel I’m pulled onto I advocate for inclusion and codesign on the basis of values – not everyone bites. So then, pulling from Yaneer’s work, I point out that hierarchies fail at the capacity of any individual, whereas examined networks can scale in complexity. They nod. I grit teeth.

We also meet Bembo and Troja Scenkonst and Billy Bottle and Anna and the Prince of the Festival Lucas, and see old friends Ben and Christopher and Smari. We walk through the cow and sheep pasture as a shortcut from breakfast to festival, avoiding dirty boots and communicating via body language to over protective rams. I jump into the half-salt water of the archipelagos after a long sauna stint, and we drink sweet Swedish cider, and we sing Flanders and Swann across our joined repertoires. Ed gives me access to his audio book library, and I’m high on dopamine and scifi for hours to come. Our tiny temporary faculty crew sleeps in adjacent cabins, keeping the floors swept and porches clean.

And another early flight, stomach dropping as the pre-booked taxi service couldn’t find us and didn’t speak English (and Sam doesn’t hold Swedish in his repository of languages), no Ubers showing up on the app as they had the previous night, and finally finding a taxi app that would generate our location and sent a lovely driver for us. Getting to the airport, again, in time, with an uncertainty of how to part ways from this other human-shaped being who moves at high velocities, having been caught up in each other’s orbits for a short period of time, still texting threads and punctuation past gates.

Dar

And then I went back to Dar. And I realize in writing this how worn down my travel-muscle is, exhausted to the core. Less able to appreciate the beauty of a second wrecked ship on a calm sandy beach, unable to see the trying and hurt at the core of some of the people we hear speak. I am frustrated that the workshop I have been flown here to participate in has people reading verbatim from slides, that at the core of this workshop are not the people who are the most marginalized. I am brief, and I am blunt, and I do not show the same care that I expect to be shown to everyone. I become even more blunt with those who are unkind to others, a sort of brute force function into civility, and I and others know it will not work.

But some of the workshop has us figuring out hairy problems like reducing the 16-digit identifier for water points to locally useful and uniquely identifiable phrases for the database lookup table. I listen while the People Who Decide These Things think their servers won’t have the troubles other servers have. And some sections have people talking about appropriate technology and inclusion. It is productive, though differently than I’m used to.

I exchange a quiet conversation in the front of a taxi that waited for us at a restaurant, a practice which I hate, on the long journey home. The driver having not said more than a word or two at a time at first, now sharing anger about high taxes and now visible payout. The roads are paid for by other countries, the buildings, the power grid… where are his tax dollars going? We talk about schools, and his sister, and about how he has no way to speak.

We work with the Dar Taarifa team, who are unfolding and learning to push back, hours into github and strange google searches and odd places to encourage and odder places to encourage disagreement. We pause for translations, and I try to bow out so they’ll operate at full speed in Swahili, rather than moving slower so that I might understand.

Oh, also:

One of my drawings ended up all over the place:

Isn't @willowbl00's stick figure explanation of targeted surveillance the best? (as used in –http://t.co/JipKempRTQ) pic.twitter.com/YIwBUoTG6j

— Morgan Mayhem (@headhntr) August 16, 2014

Morgan’s research is pretty boss, and Barton did a great job writing.

It looks like I’m going to be in Kenya in parts of October and November playing games around climate change.

This post is apparently in the memory of LJ.

Responsible Project Lifecycle

We’re thrilled to announce our first white paper, inspired by the Engine Room’s Responsible Data Forum in Oakland months ago, and with interviews with Heather, Sara, Max, and Lisha!

Responsible Humanitarian And Disaster Response Project Cycles : Embed a “kill date” on your PLATFORM. If people are using that platform, this becomes a part of the community and culture. Alternatively, create a set of stages for the platform. For example, a crisis platform could have the following stages: initial situation awareness, crisis response, early recovery, recovery, and handover. Each of these stages have different information needs and different/progressively more restrictive rules that can be applied. Stages can have expected transition dates relative to each and informed by the unique situation needs. The most important lesson to learn is that there is no easy mandate. Each event will change the needs/time required to complete tasks, and is informed by engaging and communicating with all portions of the community (mappers, in-field deployments, affected populations, etc.).

Everything Wrong With How to Write Things Up In One Entry

I was just heading back from a week in Dar es Salaam and Iringa District when a bunch of people I <3 filled up my inbox. “Have you seen this thing? Isn’t that what you’re in Tanzania for?” Yes. Which made me sigh, because all the updates about this deployment and the community development have been blogged at the Taarifa and GWOB websites. Sometimes it’s easiest to uphold the very vacuum chamber lamented, rather than do DuckDuckGo searches. Nor did the author reach out to the existing community before complaining about… the lack of community… which is amusing as those two things cover most of what the write-up is about.

But maybe I’m tired from travel. 11 hours in a car to catch a 7 hour flight that was delayed enough that I wrote this while standing in the Istanbul airport sorting out a new route to North America. And all I can think is, “is this blog entry worth my time?” But as it gets to a deeper crux, I’ll go for it. From the article, Everything Wrong in ICT4D Academia in One Research Paper:

- Focusing on Westerners: The paper starts with a long detail about a Random Hacks of Kindness hackathon that was the start of the Taarifa software. Nice enough, but they spent 2 whole pages on it – almost 1/3 of the total report.

- Focusing on Software Developers: They spend the next 2 pages of the report going into detail around Ushahidi developers and who did or didn’t commit code to github. Okay… interesting to a point, but do we really care about the standard deviation of commits per contributor

- Forgetting about Community Members: Remember the title of the paper? Well exactly 1.3 pages of the report, less than 1/3 of the total, was spent talking about the actual community impact. You know, if crowd-sourced location based reporting can improve public service provision? And they didn’t even answer the question!

The three complaints in the write-up are spot on for trends in ICT4D as a whole, and indicative of some of the points that grate at my nerves as well. But these are not new points, especially in the GWOB+Taarifa overlap, nor does it start discussion around how to walk the fine line between tech imperialism and community involvement; discussions I agree are lacking in the field. It’s the same opening cry against tech solutionism. Which Nate and I did a whole site and presentation about recently. However, the going-for-the-face-without-looking-at-what-you’re-going-for manifest in the writeup is even more grating. The comments later show that it’s a sensationalist take on… the sensationalism of the paper’s title. And unless we’re getting into ICT4PoMo (please dear god no) I don’t see how it’s a useful rhetoric. This is a paper taken out of its highly-specific academic context and then critiqued for not being broad enough. It’s extremely short and very targeted. Of course it’s going to focus on the tech, because of the forum for which it was written. But none of that context comes forth in this critique. And if we’re going to get into the analysis-of-the-thing-as-the-thing, then the writeup is spot on, as it missed community involvement in the critique, and completely lacks context. But I digress.

The world is huge, and wonderful, and more complicated than I could ever hope to understand. Projects and people and contexts change. That’s what gives me hope in the world – that all the things that bring me tiny rage (from gender ratios to spirals of conflict to vast wealth differences) can, and will change, over time, so long as we pitch in. I’ve said it before, I’ll say it again: you are not at fault for where the world is right now. You are, however, responsible for making it suck less.

That the world is so complex and nuanced also means one of my favorite things is meeting people who work on making the world suck less in a way or on a topic that I have no hope of fully understanding. Because how could I possibly understand every angle on the myriad challenges we face? By all of us approaching from different angles, but together, we have better chances of making those improvements. When I have qualms with how someone has approached a topic, I speak up to them about it. I try to understand where things are misunderstood (remember this exchange with Patrick?). So, thanks to the author for doing that. Yes to speaking up, but in order to instigate healthy debate, for the betterment of the whole community. Because people and projects and the world change. The github repos of social good hackathons are paved with good intentions, but healthy debate within the community is based on good faith.

So, as in back in the old day of blogger rings and LiveJournal, what shall we talk about – with an assumption of moving into action – next? The community involvement in Dar es Salaam? How the Iringa District Community Owned Water Source Organizations are really excited about these “innovations,” and how they’re taking lead on it? The work that GWOB does around gender equality in the tech and response space? Or should we discuss how to ensure niche academic papers have easy links to other components of the continuation of those projects? Any extra support and enthusiasm thrown at online annotation platforms is a boon to not only situations like these, but also to the museum and open access communities. Hooray for building knowledge together!

Dar pt 3

Thursday is a holiday, and so no meetings – we wake up early and head to Mkuranga District – a rural, rather than urban (like Tendale), slum. We run for the ferry, tho thankfully we don’t have to jump for it, new journalist friend Erin in tow. On the other side of the sea, we drive for hours, slipping between staring out the window and talking about interactions and plans. When we finally arrive, Msilikale talks with some women about if they’d be ok to be interviewed. We negotiate money amongst ourselves – in the US and Europe, you get paid for research subject time. Here, there’s an expectation that uzungu will provide money. I offer to buy a meal or drinks1, but it doesn’t go over. Even this is complicated, with potential larger ramifications. What expectations are we setting? Are those ok? Ethical? The lacking infrastructure and predictability isn’t just about drains and tap water, it’s also about social interaction and protocols2

We talk about sewing, and water, and responsibility. There are only wells here, and those only produce salt water, with which they clean, wash, cook, and drink. There was once a community-held water point, but it broke at some point and it wasn’t fixed. The assumption is that the government will install the infrastructure, in the same breath as a complete lack of belief that it will ever happen3. Water can only be gotten when there’s electricity.4, when it can be gotten at all.

Again, there’s no central square, no place for known dissemination of information. Everything is done by word of mouth, neighbors talking to each other. Do they ever update each other with phones? No, there’s too much worry about the cost coming back to them (or to the person they contacted). But they’d be happy to do what’s needed to bring water to their place. If mgunzu like me try to figure out things, how can we avoid being jerks5? So long as the government brings it in, they’ll work with it. Again, this weird relationship to authority.

We hang out by one of the salt-water wells while Msilikale finds a taxi6, watching people bring carts and buckets to fill up. Children throw rocks at a lizard, chase each other, drink water from the bucket used to wash clothes now hung to dry. We stand under the gas station awning during a short but heavy rain, and then pile into a car for the long journey back to Dar es Salaam. Now it’s back to interaction at the scale of organizations, but now as informed as it can be on our short time scale by interactions with humans as humans, not in aggregate for logistics. The UNHCR refugee camp in Northwest Tanzania seems most appropriate for the water sensor innovation test deployment, as it’s a closed loop. Kibaha makes the most logistical sense for the test deployment of Taarifa, as a lot of cultural work around accountability has already been done there by a potential partner organization. Mkuranga doesn’t make sense because it’s too far out, there’s no existing social infrastructure for organizations, and there aren’t plans to put in water infrastructure for awhile yet, so people would quit reporting after awhile of no results. It’s all practical, but not cold. People here feel their responsibilities, just like anywhere else.

The next morning it’s raining as we gain a blessing from the Ministry of Water – we’ll work with their water engineers on updating reports of water points7. We sit in a taxi in traffic and talk, then meet with a potential local partner who will help with social interaction and embedding – managing expectations, closing feedback loops, continual interaction for a more successful launch – or for a better understanding of a failed launch. If it works in Kibaha, we’ll try it out in Mkuranga, with more focus on the sensors than on the reporting, to ease survey fatigue. We get back in the taxi and talk more while we head back to the Ministry of Water to talk to some engineers about what they would want out of a reporting system (yay more talking to people who use Taarifa, not just read the outputs!). As the depth of the water on the road increases, the speed of the traffic decreases. Finally, concerned about even making his flight, we send Mark off in the taxi with his luggage, and I pile into a bajaj with my own suitcase. A meeting to get to, and facilitate, on my own!

Everything goes beautifully. I’ve learned to hold firm when I’m told someone doesn’t have time, or tells me they only have a few minutes. “We’ll talk again on Monday, but right now I do want 15 minutes. That’s it.” Engineer B and I end up sharing frustrations, drawing on pieces of paper, and giving a firm handshake at the end. Msilikale and I meet up, and head to my new lodging – not the fancy hotel anymore, but a friend’s-of-a-friend house. From here, I can still see birds flocking, and the sun setting over the sea, but there are also bugs and the shower is weird and it feels so much more comfortable than the fanciness. We have dinner with one of her Dutch friends, and brave traffic, and bond over growing up in the Midwest. The ensuing days are similar, with one day blissfully off. Plans for Zanzabar are trumped by epic, amazing rains. I read frivolous articles on my iPad and watch the rain roll over the sea.

In all this, the World Bank8’s hammer is money, and so everything looks like a project to fund. What makes this a complicated mess to my anti-capitalistic heart is that, indeed, many projects do need funding in the current environment. I see the “we read as much about about a grassroots thing that works as we could, and this is how we think we should do it…” All the people I’ve met within the org want a way to make the world to suck less. But these are institutions whose tools are people, and funding, and other institutions. And while they try various tactics, and sometimes make headway, in making the world suck less… they’re also held accountable for their actionsIn theory.. The difference is, the people in grassroots initiatives have to live with the reality of the failings and successes of their (and institutional) endeavors. So of course they are who I think of first. And last. And always9.

And Msilikale and I go over the drawings I did, and listen to music, and talk about all sorts of things. The power goes out, and we keep talking, the windows closed against mosquitos and the oppressiveness of the growing heat inside overwhelming. We walk in the dark to a local Indian joint, eating overly peppered food and listening to the calls to prayer out the window. The lights go out there, too, and we eat by the light of cell phones until the generators kick in. “This,” say Msilikale, “is Dar es Salaam.”

1. Worked for Kibera.

2. Scott’s Seeing Like a State is ideologically interesting, but if there’s no way to get clean water but through organized distribution of resources, such ideology gets tempered at least a bit.

3. It’s like breaking up with someone before they break up with you.

4. Mind you, this is a project with the Ministry of Water. Not Ministry of Power. This is with water. So we can only focus on water. *shakes fist at silos*.

5. Again, Msilikale mitigating anything that seems like a promise. Or hope, really.

6. Easier to negotiate price if we’re not there.

7. The hand washing tap in the MoW does not in fact produce water. Oh, the irony.

8. A World Bank innovation fund is what is supporting this initiative.

9. Not saying others don’t, simply that there sure does seem to be a lot of reminding.